Dr. W. Andrew Terrill

Summary

The political and social upheaval in the Arab World known as the Arab Spring is one of the most significant set of events to unfold in the Middle East since the fall of the Ottoman Empire following World War I. The United States seeks a democratic outcome to all of these conflicts and is also concerned about the human rights of demonstrators in countries where they are treated with brutality. Additionally, traditional U.S. concerns for the region discussed by President Obama in a May 19, 2011, address include: (1) fighting terrorism, (2) opposing nuclear proliferation, (3) supporting freedom of commerce, including commerce in oil, and, (4) supporting Israel and the Middle East peace effort. Currently, the Arab Spring has had only a limited impact on these U.S. interests. The Arab monarchies, which are allied with the United States, appear to be the least vulnerable to regional unrest (except for Bahrain) and are moving rapidly to increase the stake of individual citizens within their political systems so as to prevent serious unrest. Bahrain, by contrast, is simmering with sectarian anger after the brutal suppression of its mostly Shi’ite demonstrators. Despite this situation, the United States can probably be more helpful to Shi’ites in that country by remaining engaged with the Bahraini government which has already shown itself responsive to some U.S. concerns about building an inclusive society.

The political and social upheaval in the Arab World known as the Arab Spring is one of the most significant set of events to unfold in the Middle East since the fall of the Ottoman Empire following World War I. The United States seeks a democratic outcome to all of these conflicts and is also concerned about the human rights of demonstrators in countries where they are treated with brutality. Additionally, traditional U.S. concerns for the region discussed by President Obama in a May 19, 2011, address include: (1) fighting terrorism, (2) opposing nuclear proliferation, (3) supporting freedom of commerce, including commerce in oil, and, (4) supporting Israel and the Middle East peace effort. Currently, the Arab Spring has had only a limited impact on these U.S. interests. The Arab monarchies, which are allied with the United States, appear to be the least vulnerable to regional unrest (except for Bahrain) and are moving rapidly to increase the stake of individual citizens within their political systems so as to prevent serious unrest. Bahrain, by contrast, is simmering with sectarian anger after the brutal suppression of its mostly Shi’ite demonstrators. Despite this situation, the United States can probably be more helpful to Shi’ites in that country by remaining engaged with the Bahraini government which has already shown itself responsive to some U.S. concerns about building an inclusive society.

Conversely, there is considerable unrest in the non-monarchial countries of Syria, Libya, and Yemen. The United States has no reason to become seriously involved in the conflict in Syria and no interest in expanding its involvement in the conflict in Libya at this point. Washington does however have an interest in helping to bolster moderate elements within successor governments to either of these regimes. In this regard, the suspected Islamist and terrorist associations of various Libyan rebels have been the subject of concern. While some of these individuals might have been simple patriots willing to work with any organized force opposing the Qadhafi regime, others may be hard core Islamists that are at least a potential danger to any future Libyan democracy as well as the interests of the United States and the other Western democracies.

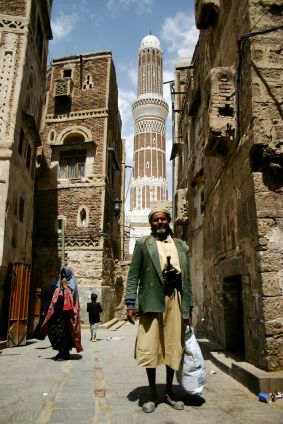

The United States also maintains a serious interest in the outcome of the civil unrest in Yemen, which is the headquarters of a particularly formidable branch of al-Qaeda. This organization known as al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) has attempted two serious although ultimately unsuccessful terrorist strikes against the U.S. homeland and is flourishing in Yemen’s current environment of chaos. Support for a friendly Yemeni government after the anticipated fall of President Ali Abdullah Saleh is therefore vital. It will be particularly problematic if Yemen splits into numerous independent or quasi-independent states, which is a clear possibility. Washington will also have to remain vigilant about disrupting other opportunities for terrorists that may be presented elsewhere in the region within the more turbulent environment. U.S. officials must continue to maintain strong ties with friendly intelligence services such as the General Intelligence Directorate in Jordan as well as the Saudi intelligence service. Such links are particularly important since some intelligence ties with Egypt and perhaps Tunisia appear to have been disrupted by the revolutions in those countries. U.S. intelligence agencies will need to respond to these setbacks by seeking ties with post revolutionary governments in Tunisia, Egypt, and elsewhere to the extent that such states can be reliable partners.

In the above context, the future of Egypt and Iraq are still very much unresolved and the U.S. alliance with both countries is subject to this uncertainty. The post-Mubarak government in Egypt is currently struggling to define itself and to plan for free elections. The United States military needs to remain engaged with Cairo and recognize that other states in the region that are also working to encourage moderation and restraint by the Egyptian revolutionaries. In contrast, Iraq has only been influenced by the Arab Spring to a limited extent so far, although demonstrations against corruption in Iraqi cities were probably influenced by the Egyptian example. Nevertheless, sectarian tension elsewhere in the region occurring in places such as Bahrain may continue to have a negative impact on Iraq’s already divisive politics. As U.S. troops withdraw from Iraq, Baghdad will continue to face ongoing difficulties building a unified, inclusive, and prosperous nation and will require continuing U.S. financial and diplomatic support. Under all of these circumstances, it is also clear that U.S. policies will also have to remain, flexible and responsive to the rapidly unfolding events still to come throughout the region.

Introduction: U.S. National Interests and the Arab Spring

The political and social upheaval in the Arab World known as the Arab Spring is one of the most important set of events to unfold in the Middle East since the post-World War I fall of the Ottoman Empire. Nevertheless, the Arab Spring is not a trend with a predictable let alone inevitable positive result. Rather, it is a regionwide set of developments which are reflected in highly different ways in a variety of Arab countries. The rapid and spectacular ouster of an ossified and corrupt Tunisian dictatorship in January 2011 stunned the world and raised the possibility that many other Arab regimes were not as deeply entrenched as they might appear. Tunisia’s revolution then helped ignite an 18-day upheaval in Egypt that led to President Hosni Mubarak’s resignation on February 11. The 83 year old former president is scheduled to go on trial on August 3 on charges of corruption and the intentional murder of demonstrators. His two sons also face similar charges. After the Mubarak government’s collapse, Arab revolutionaries seeking change elsewhere faced a much more difficult set of problems. A mass uprising in Libya was met with a brutal and unrelenting response that led to limited NATO military intervention.1 Bahraini demonstrators threatened to overwhelm the government with their demands and were then met with a March 14, Saudi Arabian-led, military intervention that has pushed the situation down to a slow burn. Syria and Yemen now appear to be in the early stages of civil war and a variety of other Arab countries are uncertain how they may be influenced by the Arab Spring in the future. Even national leaderships outside of the Arab World including Iran and perhaps even China are reported to be concerned that the Arab Spring is setting a troubling example for their own populations.

The political and social upheaval in the Arab World known as the Arab Spring is one of the most important set of events to unfold in the Middle East since the post-World War I fall of the Ottoman Empire. Nevertheless, the Arab Spring is not a trend with a predictable let alone inevitable positive result. Rather, it is a regionwide set of developments which are reflected in highly different ways in a variety of Arab countries. The rapid and spectacular ouster of an ossified and corrupt Tunisian dictatorship in January 2011 stunned the world and raised the possibility that many other Arab regimes were not as deeply entrenched as they might appear. Tunisia’s revolution then helped ignite an 18-day upheaval in Egypt that led to President Hosni Mubarak’s resignation on February 11. The 83 year old former president is scheduled to go on trial on August 3 on charges of corruption and the intentional murder of demonstrators. His two sons also face similar charges. After the Mubarak government’s collapse, Arab revolutionaries seeking change elsewhere faced a much more difficult set of problems. A mass uprising in Libya was met with a brutal and unrelenting response that led to limited NATO military intervention.1 Bahraini demonstrators threatened to overwhelm the government with their demands and were then met with a March 14, Saudi Arabian-led, military intervention that has pushed the situation down to a slow burn. Syria and Yemen now appear to be in the early stages of civil war and a variety of other Arab countries are uncertain how they may be influenced by the Arab Spring in the future. Even national leaderships outside of the Arab World including Iran and perhaps even China are reported to be concerned that the Arab Spring is setting a troubling example for their own populations.

The United States is interested in a democratic outcome to all of these conflicts and is also concerned about the human rights of demonstrators in countries where they are treated with brutality. In addition to these concerns, Washington must weigh its other interests and priorities for the region which may be influenced by the Arab Spring in both positive and negative ways. In a May 19, 2011, speech on the Middle East and North Africa, President Barack Obama identified what he called four “core interests” in the region. According to the President these are: (1) “countering terrorism,” (2) “stopping the spread of nuclear weapons,” (3) “securing the free flow of commerce and safeguarding the security of the region,” and, (4) “standing up for Israel’s security and pursuing Arab Israeli peace.”2 The U.S. military and intelligence presence in this region is designed to support these objectives and to reassure U.S. allies while deterring potential adversaries such as Iran. Currently, it is not clear if the Arab Spring will require the U.S. military to find dramatically new ways to protect these interests or what kind of adjustments to U.S. basing and force structure may be required in this new era. It is nevertheless useful to consider possibilities and scenarios as this process unfolds, and it is also worthwhile to consider what potential outcomes are most likely. In making such an analysis, all relevant states must be considered including the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) monarchies, the republican governments under siege (Yemen, Syria, Libya), and post-revolutionary Egypt. The Arab Spring may also have important implications for Iraq, where U.S. troops are currently scheduled to depart in December 2011. Iran may be able to take advantage of the Arab Spring or it may face domestic problems because of the influence of the Arab Spring on the Iranian population.

In an insightful if sardonic comment, leading Middle East military analyst Anthony Cordesman has stated that the primary export of this region is blame.3 This statement particularly applies to the United States. The United States will probably be heavily criticized by regional opinion leaders no matter what it does or fails to do in response to the Arab Spring. Many of the regional opinion leaders making charges against Washington will be the same regardless of the policy, although they may vary the level of shrillness based on actual political preferences. Moreover, intense U.S. involvement in any crisis will usually be denounced more intensively than aloofness (which will also be criticized). Arab public opinion usually has a default position of opposing Western intervention anywhere in the region, but there are exceptions. To some extent, the creation of a United Nations sponsored No-Fly Zone (NFZ) over Libya was one of these exceptions, since it was preceded by an Arab League call for such a measure, and the U.S. only played a limited and brief combat role before other states assumed the most high visibility operational combat roles. Leading Arab nations such as Egypt and Saudi Arabia have not participated in the NFZ, although some smaller Arab states have done so, and Qatar has been so involved with helping the Libyans it has emerged as something of a “hero-nation.”4

At the present time, the U.S. military presence in the Arab World has not been significantly impacted by the Arab Spring, although the Bright Star set of exercises with Egypt face an uncertain future. The United States maintains a significant military presence at facilities in Bahrain, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar. None of these states have faced serious unrest except Bahrain which was nearly engulfed in confrontations between the authorities and demonstrators. Small wealthy states within the GCC clearly view U.S. bases as an important source of protection from bullying and perhaps even military invasion by larger regional neighbors such as Iran. To an extent some even worry about the future leadership of Iraq. The requirement for an external guarantor to protect the independence of these states is almost a systemic feature of the Gulf region which will be difficult for successor regimes to alter unless they become so radical in a post-monarchical scenario that ideology requires them to place themselves at the mercy of their larger Gulf neighbors. Additionally, the United States provides foreign military sales to all of these countries and to a variety of other U.S. allies in the region as well. Especially massive arms sales are currently planned for Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Moreover, Bahrain, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, and Morocco have been designated as “major non-NATO allies,” a special status which allows them preferential access to U.S. military aid and equipment. The United States withdrew combat forces from Saudi Arabia in 2003, although the Saudis remain closely allied with the United States and Riyadh has accelerated their purchase of U.S. weaponry.5 Saudi Arabia and the United States are currently negotiating a $60 billion arms package.

U.S. Concerns about the Bahraini Uprising and the future of the Arab Monarchies

One of the most significant Arab Spring concerns for the United States involves the future of the small island nation of Bahrain. Bahrain has been a longtime U.S. ally and currently serves as the headquarters of United States Naval Forces Central Command (U.S. NAVCENT) and the U.S. Fifth Fleet. Bahrain however is the most problematic of the Gulf Arab allies due the government’s brutal repression of pro-reform demonstrators who are overwhelmingly drawn from that country’s Shi’ite majority. As a result of these violent actions, some commentators have called for the United States to withdraw the Fifth Fleet from Bahrain as a sign of U.S. anger over the repression and to challenge the legitimacy of the regime. These calls for a strong response are understandable, but at least at this stage such actions would probably be a mistake. Bahrain, which has very little oil, is quite close to becoming an economic dependency of Saudi Arabia, and the leadership there seeks other allies to prevent a total dependence on Riyadh. The Bahraini leadership is also deeply worried about Iran with which it shares an uneasy history.6 These factors have caused Bahrain to remain interested in good relations with the West and especially the United States leaving some potential for Washington to moderate Bahrain’s behavior.

Bahraini interest in maintaining good relations with the United States has already yielded some positive results. In April 2011, the government moved to have the Wafaq party and the Islamic Action Association, a smaller Shi’ite party banned.7 Wafaq is the largest political party in Bahrain, and held 18 of the 40 seats in the lower (elected) house of the Bahraini parliament when unrest broke out on February 14, 2011. To outlaw it would have been a severe blow against even nominal democratic representation as well as a further escalation of hostility against Bahrain’s Shi’ites. While this move to destroy limited Shi’ite political representation was almost certainly viewed with approval by Saudis, the United States reacted with concern and defended the embattled organizations as legitimate political parties which were struggling for reform by legal means. Consequently, the Bahraini government quickly reconsidered its position and movement towards outlawing these parties seems to have halted.8 In this regard, the Bahraini government continues to value good relations with the United States even though its most important foreign policy ally remains Saudi Arabia. It is probable that Bahrain’s monarchy would continue to seek some sort of potential counterweight to Saudi influence to prevent their further decline into complete satellite status. Additionally, the Bahrainis will continue to value U.S. cooperation against Iran and view the presence of the U.S. Fifth Fleet headquarters in Bahrain as an important deterrent limiting Iran’s options against them. Bahrain is within eight minutes flying time from Iran, and concerns about Iran are central to Manama’s assessments of possible dangers to its independence and security. While breaking military ties with the Bahraini government might provide a morally uplifting moment for the United States, it would undermine U.S. influence there and could make life even more difficult for the Bahraini Shi’ites. In the interests of Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the United States, U.S. policy needs to push the Bahraini government into remolding the economic system there so that it provides Shi’ites with a stake in the system. If economic reform takes place political reforms may become more possible in a more stable domestic environment.

Arab monarchies are currently doing better at controlling instability and limiting economic despair than the dictatorial republics rocked by unrest, with the exception of Bahrain which is still simmering even after the Saudi-led intervention. Most of these monarchical governments appear to be viewed as legitimate by significant elements of their highly conservative population. The most significant problem these regimes face may be corruption which sometimes threatens to sap the confidence of the population in their government.9 Since the beginning of the Arab Spring, a variety of Arab monarchies have sought to provide more economic benefits to their populations including higher salaries in their bloated public sectors and more welfare benefits for the public at large. The object of this exercise is clearly to give people a larger stake in the future of the political system. While many political demands have characterized the Arab uprisings, some of these confrontations have been profoundly influenced by economic problems, particularly poverty and unemployment. In the absence of these economic problems, it is uncertain that the unrest in Egypt and Tunisia would have reached regime-threatening levels.

Interestingly, two of the poorest monarchies in the Middle East are being supported by the wealthiest, and the level of interest in helping these governments has risen as a result of the Arab Spring. Jordan and Morocco were both offered full membership in the Saudi-led Gulf Cooperation Council in May 2011, despite their lack of proximity to the Gulf (especially for Morocco).10 Such membership offers a variety of economic advantages which will help both countries maintain a higher level of economic development. Both Jordan and Morocco have experienced protests inspired by the uprising in Egypt, but these protests have not been regime threatening and focused on reform rather than revolution. The protests also faded over time, although the example of unexpected and rapidly expanding unrest in other countries has probably contributed to the GCC effort to immunize these nations from regime-threatening unrest. In general, the overthrow of any monarchy is viewed with horror by the current GCC states because such an action is viewed as the worst possible example for their own populations. No Arab king wishes to see himself as the last quaint anachronism in a region that has moved beyond monarchy. Also the history of the Middle East has yet to produce a fully democratic government in the aftermath of an ousted monarchy. Instead it has often produced brutal dictatorships. In Iraq, for example, the 1958 ouster of a moderate Hashemite monarchy led to a series of brutal strongmen culminating in the rule of Saddam Hussein.

The viability and basic well-being of most Arab monarchies has been of value to the United States in fighting terrorism. Saudi Arabia is one of al-Qaeda’s most bitter adversaries following a wave of terrorism in the kingdom led by al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) from 2003-2009. AQAP was defeated in Saudi Arabia by 2009, but fled to nearby Yemen were it remains a threat, and where Saudi Arabia has supported measures to destroy the organization to the extent it has been able. Jordan is also a bitter enemy of al-Qaeda. The terrorist organization attempted to assassinate Jordanian King Abdullah in the Greek Islands in 2000 and made another series of strikes against Jordanian targets in the years that followed.11 This process reached its zenith in November 2005 in an attack on three Amman hotels in which 62 people were killed by suicide bombers. Agents of the Jordanian General Intelligence Directorate (GID) have been deeply involved in efforts to defeat al-Qaeda since well before these events, and their efforts have surged in later years.12 It is also noteworthy that the Saudi and Jordanian intelligence have become significantly more valuable to the United States as a result of the Egyptian revolution which has disrupted previously strong intelligence ties with Cairo.13

Republican Regimes in Crisis: Syria, Libya, and Yemen

While most of the monarchical allies of the United States do not appear to be facing serious upheaval at the present time, three non-monarchies which call themselves republics are facing extremely serious unrest.14 These are Syria, Libya, and Yemen. Syria and Libya do not have a history of close cooperation with the United States, although it has sometimes been possible for these states to work with Washington on specific issues and concerns. At other times, various U.S. Administrations have viewed them as closer to being “rogue states.” Both of these states have nevertheless opposed al-Qaeda, while Libya has verifiably ended its nuclear weapons program in response to Western pressures.15 The United States retains stronger ties with Yemen, although the Sana’a government has often been described as a difficult ally for a variety of reasons including President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s occasional desire to avoid offending Islamist opinion in his country by limiting cooperation with the United States. On the positive side, Yemen has played a useful role in opposing AQAP, which has been a domestic threat to the Yemenis as well as a committed enemy of the United States and Saudi Arabia. It is doubtful that this effort will continue at the same level now that Yemen is facing a prolonged civil crisis and the central government’s only priority is to survive.

While most of the monarchical allies of the United States do not appear to be facing serious upheaval at the present time, three non-monarchies which call themselves republics are facing extremely serious unrest.14 These are Syria, Libya, and Yemen. Syria and Libya do not have a history of close cooperation with the United States, although it has sometimes been possible for these states to work with Washington on specific issues and concerns. At other times, various U.S. Administrations have viewed them as closer to being “rogue states.” Both of these states have nevertheless opposed al-Qaeda, while Libya has verifiably ended its nuclear weapons program in response to Western pressures.15 The United States retains stronger ties with Yemen, although the Sana’a government has often been described as a difficult ally for a variety of reasons including President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s occasional desire to avoid offending Islamist opinion in his country by limiting cooperation with the United States. On the positive side, Yemen has played a useful role in opposing AQAP, which has been a domestic threat to the Yemenis as well as a committed enemy of the United States and Saudi Arabia. It is doubtful that this effort will continue at the same level now that Yemen is facing a prolonged civil crisis and the central government’s only priority is to survive.

Prior to the beginning of the Arab Spring, the Syrian regime appeared to be the most deeply entrenched of the republican governments currently under siege. This strength now appears to have been an illusion as Syrian protestors repeatedly accept large numbers of casualties to challenge the government. Additionally Syria’s escalating civil unrest has a strong sectarian character in which the Alawite-dominated government and military is increasingly challenged by Sunni Muslim protesters and at least to some extent by military deserters.16 In this struggle, the Syrian opposition forces are aware that they will never remove the Assad regime from power with peaceful protests so their best and perhaps only hope is to realign the Sunni elements of the military with the protesters. Sunni Muslims comprise 75 percent of the Syrian population whereas Alawites are only around 8-10 percent. If large numbers of Sunni soldiers change sides and join the rebels, they will then have the numbers to start effectively fighting back against elite Syrian units composed of Alawites who are deeply loyal to Assad. The most important of these units are the Republican Guard and the 4th Armored Division.

Even under the most optimistic scenarios for the Syrian opposition, armed struggle against the regime will still be extremely tough since the elite units have much better training, weapons, and equipment than the non-elite units. Non-elite units also have Alawite officers filling most of the key command and staff positions even though the balance of the troop strength is made up of Sunni conscripts. If Sunnis in non-elite units did successfully mutiny they would still face a number of challenges. In the process of taking power, rebels would have to arrest or kill the majority of the unit’s key officers. Successful mutineers would then have to put together a new chain of command and reorganize their units in ways that are unlikely to measure up to the organizational structure and efficiency of loyalist forces. Under these conditions, the prospects for a long and bloody civil war appear increasingly serious. It is uncertain if other Sunni Arab states will become involved by supporting the rebels with arms and funds. Iran has already provided some support for the Damascus government with advice and technical expertise on riot control and suppressing demonstrations.17 The Iranians may have provided other forms of support as well. The problem for the opposition is that the army has not started to unravel and thereby begin a process that can gather momentum and spread to a variety of other army forces. On the basis of the limited information available, it still appears that Sunni troops are deserting the military but they are still doing so as individuals or in small groups. No officers above the rank of captain are known to have joined the rebels, although one lieutenant colonel has fled to Turkey from northern Syria rather than continue to serve the regime.18

The situation is most likely to evolve in one of two ways. Either the regime will grind down the opposition with brutality and eventually overcome it while facing no more than limited defections or real military unrest will develop in the army and it will unravel. Syria has an army of 220,000 troops of which about 175,000 are conscripts serving 30 months of national service.19 It is still unclear what threshold would have to be crossed in order for mass defections to start occurring to the point that other Sunni conscripts would view defection to the rebels as a more viable option. Many ordinary Syrian soldiers may view themselves as closer to prison inmates than people with real options about how to change their lives let alone their country. The final acid test would be if troops felt that by their defection they could help defend their own homes and communities should these come under attack by the government. In that case, they would come under enormous psychological pressure to desert the army if they had a viable plan for what to do afterwards. Nevertheless, it is not clear that they could escape from the army in such a way as to form the nucleus of a viable resistance to the regime. The Syrian regime’s extensive use of torture is well-known and one can probably assume that captured deserters are treated harshly prior to their execution and that the rest of the military is aware of this situation. In summary, the Syrian resistance has to reach a “critical mass” whereby it looks like it has a real chance in an armed struggle, and once this occurs we can reasonable expect to see large numbers of people rally to the opposition and face down the Syrian regime in a comprehensive armed struggle. If the Syrian regime can prevent this turning point from being reached, it can suppress the disparate and disorganized opposition forces.

The uprising and potential civil war in Syria is an instance where the United States could cause more problems than it would solve by becoming involved beyond the level of diplomatic actions and economic sanctions. While current U.S. priorities and concerns probably rule out a U.S. military presence, there may still be considerable political pressure for the U.S. to take actions short of war. In extreme cases, this could imply providing weapons, intelligence, or even training to rebels in Syria who are fighting against the Assad regime. Such actions need to be treated with the upmost caution to avoid drawing the United States into a sectarian conflict that can be expected to be at least as problematic as the 2006 difficulties in Iraq. Washington also might want to remain in the background so as not to play into the Syrian government’s narrative that the rebellion is the result of a U.S., Israeli, and Lebanese Christian conspiracy against them. The United States may choose more reasonably to provide aid and support for Syrian refugees who flee across regional borders. These actions could probably be done most effectively by working through international humanitarian organizations and foreign governments. Additionally, if other Sunni Arab states wish to support the Syrian rebels the United States has no real interest in preventing them from doing so.

The uprising and potential civil war in Syria is an instance where the United States could cause more problems than it would solve by becoming involved beyond the level of diplomatic actions and economic sanctions. While current U.S. priorities and concerns probably rule out a U.S. military presence, there may still be considerable political pressure for the U.S. to take actions short of war. In extreme cases, this could imply providing weapons, intelligence, or even training to rebels in Syria who are fighting against the Assad regime. Such actions need to be treated with the upmost caution to avoid drawing the United States into a sectarian conflict that can be expected to be at least as problematic as the 2006 difficulties in Iraq. Washington also might want to remain in the background so as not to play into the Syrian government’s narrative that the rebellion is the result of a U.S., Israeli, and Lebanese Christian conspiracy against them. The United States may choose more reasonably to provide aid and support for Syrian refugees who flee across regional borders. These actions could probably be done most effectively by working through international humanitarian organizations and foreign governments. Additionally, if other Sunni Arab states wish to support the Syrian rebels the United States has no real interest in preventing them from doing so.

As with Syria, Washington has no vital interests in Libya. The United States maintains extremely limited economic interaction with the Libyans, and Libya is no longer a nuclear proliferation theat. Conversely, 85 percent of Libyan oil exports go to Europe, giving some European states a much higher stake in the outcome of the Libyan civil war than the United States. Washington intervened reluctantly in Libya and did so only after it became apparent that the 800,000 people of the city of Benghazi almost certainly faced a bloodbath if forces loyal to Libyan dictator Colonel Muhammar Qadhafi seized the city.20 This humanitarian gesture was made easier by the use of airpower and standoff munitions to halt Qadhafi’s offensive against Benghazi. The United States then turned leadership of the NFZ to NATO with France and the United Kingdom playing the leading roles in the air campaign in a reflection of their deeper interests in Libyan oil. To date, no American or NATO service member has died in the Libyan operation, and there are no prospects for future American casualties since the U.S. combat role is currently limited to unmanned predator drones. The only friendly casualties have been Libyan rebels supporting the Transitional National Government (TNG).

The U.S. and NATO Libyan intervention, which began on March 19, 2011, has lasted for longer than many in the West expected. It also appears increasingly unlikely that Qadhafi will ever leave Libya and will more probably choose to die there rather than go into exile. The Libyan dictator has a deeply inflated view of his role as the leader of the revolution and as a vanguard international visionary. Rather than watch his 40 years of revolutionary efforts collapse, he will probably choose to remain in Libya if he sees even a sliver of hope that he might remain in power. Qadhafi may hope that the West will become exhausted by longer than expected efforts to overthrow the regime and therefore agree to some sort of negotiated solution. There is also a possibility of rebel infighting or that the rebels will at some point run out of funds to support their alternative government. To date, they have been chronically short of income and have been helped immensely with loans from Qatar, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates.21 It is not clear how long these loans will continue to be provided to the rebels or if they will be able to acquire Libyan funds frozen in Western financial institutions. While de facto partition would be a negative outcome for the Libyan regime, the current leadership would still view this as better than a scenario where Qadhafi was forced to flee the country. Qadhafi may also believe that Western oil companies will at some point purchase his oil again. It is unclear how much financial wherewithal the regime maintains, but one informed source claims Qadhafi has around $10 billion inside the country.22

While Qadhafi clearly retains some hope, the course of events seems to be going against him. Increasing numbers of countries are recognizing the Transitional National Government (TNG) and this recognition lays the groundwork for transferring Libyan funds to them. Additionally, a steady number of top Qadhafi regime officials have continued to defect from the government. NATO, for all its problems, is conducting an air campaign that is eroding regime military strength and the rebels have acquired increased weaponry and training. Qatar and the UAE are supporting the TNG in both of these endeavors with vast sums of money.23

It is doubtful that the United States will increase its military involvement in Libya especially as the Qadhafi regime appears to be weakening. The chief U.S. concern for Libya in the aftermath of a Qadhafi collapse will be to prevent it from becoming a radical country serving as a haven for terrorists. Christopher Boucek of the Carnegie Endowment has noted that a number of Islamists have been released from prison or escaped as a consequence of the revolutionary activity in Libya.24 Some of these individuals are deeply committed ideologues and there is now more political space for them to organize. Dr. Boucek has also maintained that there have been large numbers of imprisoned Islamists in Libya, since they were previously the chief threat to the regime. He also noted that Libya’s rehabilitation programs for Islamists have been a failure and that the Islamists were defeated by repressive means alone. This creates a larger pool of individuals to help form a challenge to any emerging Libyan government. Struggling against this outcome is probably something that can best be done with “soft power” rather than military intervention. Soft power, in this instance, might include economic cooperation with a new Libyan government as a reward for moderate policies. The United States may also be well advised to help set up a meaningful counterterrorism program for post-Qadhafi Libya if it appears that such a government will be a reliable partner.

The United States government is more directly involved with Yemen than either Syria or Libya, and Washington policymakers tend to view events there with more alarm than the crises in either Libya or Syria. Yemen has emerged as one of the central fronts in the struggle against terrorism due to the activities of AQAP. Washington has maintained a significant aid program directed at Yemen, but it is not Yemen’s most important foreign partner. Saudi Arabia provides much more aid and has much more clout with both the embattled Saleh regime as well as many of the major Yemeni tribes. It seems likely that the Yemenis are more focused on the messages they are getting from Riyadh than Washington. One of the most well-known al-Qaeda operations took place on December 25, 2009, when an operative trained in Yemen attempted to blow up a Northwest Airline passenger jet with 280 people aboard. In response, Yemen quickly announced that it has arrested 29 people believed to be members of al-Qaeda in a domestic crackdown on that organization.25 Later, in 2010, AQAP again sought to attack targets within the United States. In that incident, two parcel bombs were to be sent to Jewish organizations in Chicago. The operation was foiled due to a timely warning from the Saudi intelligence, which as noted aggressively seeks information on AQAP in the hopes of destroying the organization.26

There are also emerging signs that AQAP operations against the government may be taking on a new and more virulent form. While AQAP’s interest in spectacular acts of terrorism constitutes a frightening threat, it would be a mistake to focus on these activities in ways that gloss over the organization’s progress in challenging the government within Yemen itself. Whereas AQAP has often been viewed primarily as a terrorism organization, it may well be emerging as more than that now. In particular, AQAP is potentially rising as an insurgent group willing to wage guerrilla war and contest control of portions of the Yemeni hinterland with the Yemeni government. One of the most dramatic indications of AQAP’s increased willingness to fight as an insurgent force can be seen during August 2010 combat operations in the southern town of Loder. At this time, AQAP established a strong presence in the town of 80,000 people to the point that the Yemeni army felt required to distribute pamphlets requiring the residents to leave the urban center prior to a forthcoming battle.27 While al-Qaeda was expelled from Loder at that time, AQAP and its allies seized the town of Zinjibar in southern Yemen in May 2011. To date, the Yemeni government has been unable to drive it out.28

The current President of Yemen, Ali Abdullah Saleh, was wounded in a rocket attack against the palace and flown to Saudi Arabia for surgery on June 4. Since then it has become clear that his wounds were serious and that Riyadh does not wish Saleh to return to Yemen to try to rebuild his shattered regime, now led by his sons and nephews.29 As the fighting in Yemen continues and after Saleh’s departure appears to be permanent, it is increasingly possible that Yemen will divide into multiple states. It is unclear how many states Yemen may fragment into, although the establishment of two or three separate states is the most likely outcome. In southern Yemen there is a strong independence movement which could well come to the forefront of Yemeni politics should the government in the north lose its capacity to pressure the regions of the country. Likewise the Hadhramaut, which was once part of the Peoples Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY), may also seek independence. This is also possible with areas of the north which are dominated by Yemen's fiver Shi’ites, often referred to as Houthis after the leading family in that region.30 Houthi forces have periodically been at war with government forces, although they have never announced a clearly secessionist agenda. It is also possible that a variety of Arab tribes would behave as autonomous political entities without formally declaring independence should Yemen become a failed state.

The possibility of Yemen breaking into multiple states or autonomous substates that are not controlled by any central government represents a potentially serious problem. Fighting terrorism could be enormously complicated by the need to deal with multiple centers of authority. Terrorist groups, such as AQAP, seeking support and sanctuary may have more options to choose from. While many terrorists have often viewed Yemen as a suitable place to operate and rebuild for years, it could become significantly worse in the absence of even a weak central government.

Unresolved and Evolving Regional Roles and Issues: Post-Revolutionary Egypt, Iraq, and Iran

The future of Egypt is still very much unresolved and needs to be considered as well. The U.S. alliance with Egypt is part of this uncertainty. The post-Mubarak government is currently struggling to define itself and to plan for free elections. A number of commentators have expressed concern that the new Egyptian government might come under the sway of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood and ally itself with Iran. While anything can happen in elections, any future Egyptian government has a tremendous stake in seeking pragmatic solutions for its economic problems. Tourism and foreign investment from the West virtually collapsed in the aftermath of the revolution and are now only being re-established at exceptionally low levels. President Obama has noted that the United States will continue to provide aid to Cairo but with its own budget crisis there is only so much that Washington is able to do. Several Gulf Arab states have stepped into this void, but it is difficult to believe that they would continue to support Egypt if it established close ties to Iran. The Saudi-led military intervention in Bahrain has provoked an escalation in the already high level of tension that exists between the GCC and Tehran to the point that serious Egyptian-Iranian cooperation would help undermine Cairo’s relations with the Gulf. In addition, Iran does not seem popular with the Egyptian public and the Iranian form of government is held in extremely low regard by Egyptians according to a variety of public opinion polls.31

Iraq has only been influenced by the Arab Spring to a limited extent so far, although demonstrations against corruption in Iraqi cities were probably influenced by the Egyptian example. Some Iraqi Shi’ites also demonstrated in angry solidarity with Bahraini protestors who were violently suppressed by the authorities. As U.S. troops withdraw from Iraq, Baghdad will continue to face ongoing difficulties building a unified, inclusive, and prosperous nation. Powerful sectarian tension may become more pronounced in Iraq following a U.S. military withdrawal, and these concerns will add to the problems for any Iraqi government seeking to hold the country together. Unfortunately, the sectarian nature of some of the Arab Spring conflicts is unlikely to have a calming effect on the Iraqi population. Sectarian anger has already provoked strong Iraqi Shi’ite demonstration against the Bahraini government. Prime Minister Maliki is already viewed by many Sunnis throughout the region as a sectarian figure, and ability to prevent renewed fighting among Iraqi sects is uncertain. U.S. diplomacy remains necessary to help support any Iraqi efforts at national reconciliation.

Additionally, it might be noted that Iran is vigorously interested in exploiting the Arab Spring but has so far achieved little success in doing so. Early in the Egyptian crisis, Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei made enthusiastic statements endorsing the Egyptian protesters and attempting to portray events in that country as an Iranian-style revolution likely to lead to an Egyptian Islamic republic.32 He further stated that regionwide regime-changing upheaval and demands for Islamic government were natural extensions of Iran’s 1979 revolution. Such remarks are fundamentally wrong but not necessarily delusional. Rather, the Iranian leaders are seeking to indicate to their population that Iran was the first country to overthrow an autocrat in this process and that it is not a country that requires a revolution to get rid of a corrupt political system or corrupt leaders. Clearly many Iranians who were part of the 2009 Green Movement that protested the falsified re-election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad may view things differently. While many of these people may not yet have given up on the concept of an Islamic Republic, they clearly view the current political leaders as fraudulent and corrupt.

Conclusion

At this point in time, the Arab Spring has only had a limited impact on U.S. interests in the Middle East. The future of many Arab countries nevertheless remains difficult to sort out and the Arab uprisings and their aftermath will be a feature in the regional landscape for the foreseeable future. The United States needs to remain careful about inserting itself too forcefully into these regional problems. Military intervention in Syria for example would be a high risk/ low potential payoff effort. The United States should continue to be limited and careful in the ways that it relates to these events. Other nations, including small but wealthy Qatar and the UAE, have already stepped forward to help the Libyan rebels with finances, weapons, supplies, and training in the absence of U.S. efforts to dominate the crisis. It remains likely that U.S. regional allies can play more productive roles than the United States itself can in a region that is deeply sensitive about U.S. military intervention.

Additionally, U.S. access to the region has not been threatened by the Arab Spring, and the Arab revolutionaries may well set up regimes that are both friendly to the United States and more supportive of domestic human rights. If these new governments are able to raise the standard of living within their countries this will have a potentially significant long-range value for preventing terrorism. The United States will however have to remain vigilant about opportunities for terrorists that may be presented in a more turbulent environment. It must also maintain strong ties with friendly intelligence services such as the General Intelligence Directorate in Jordan and restore such ties with post revolutionary governments in Tunisia, Egypt, and elsewhere to the extent that such states can be reliable partners. U.S. policy will also have to remain, flexible and responsive to unfolding events. The criticism that the United States is inconsistent and responds differently to revolutionary situations in a variety of countries is true, but the basis for the complaint is nonsense. Any action of this type in the current regional environment requires a careful cost/benefit analysis within the context of U.S. national interests. An intervention in Libya does not require an intervention in Syria for the sake of consistency. Serious observers can only wince at such “logic.”

Endnotes

1. On Libyan brutality see Human Rights Watch, “Libya: Cluster Munitions Strike Misrata,” April 15, 2011, www.hrw.org.

2. Office of the White House Press Secretary, “Remarks by the President on the Middle East and North Africa,” May 19, 2011, www.whitehouse.gov.

3. Ross Jackson, “US cannot be expected to solve the region’s problems,” Gulf Times, May 12, 2011.

4. Portia Walker, “Qatar Gets Libyan Opposition into Shape,” Washington Post, May 13, 2011; Doyle McManus, “Breaking Point in Libya,” Los Angeles Times, April 24, 2011; “1st Arab Country to fly over Libya,” Kuwait Times, March 27, 2011, Agence France-Presse, “Qatar in spotlight in absence of Arab Heavies,” Gulf in the Media, March 31, 2011.

5. “US pulls out of Saudi Arabia,” BBC News World Edition, April 29, 2003.

6. Iran under the last shah and under revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini claimed Bahrain was historically and legally part of Iran. More recent leaders have not revived these claims officially although a newspaper editor with close ties to the Iranian leadership did question Bahrain’s independence from Iran. J.B. Kelly, Arabia, The Gulf and the West, New York: Basic Books, 1980, pp. 54-55; Anthony H. Cordesman, Bahrain, Oman, Qatar, and the UAE, Challenges of Security, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1997, p. 41, Kimia Sanati, “US presence fuels Iran-Bahrain tension,” Asian Times Online, July 19, 2007.

7. Joby Warrrick and Michael Birnbaum, “Questions as Bahrain Stifles Revolt,” Washington Post, April 15, 2011.

8. Kristen Chick, “Bahrain backs off plan to ban opposition after U.S. criticism,” Christian Science Monitor, April 15, 2011.

9. There is for example considerable recent turmoil in the Kuwaiti parliament over perceived government corruption. See “Amir warns against chaos, calls for unity,” Kuwait Times, June 16, 2011.

10. “Jordan, Morocco to join GCC,” Khaleej Times, May 11, 2011; ”GCC welcomes Jordan, Morocco membership,” Kuwait Times, May 11, 2011.

11. King Abdullah II of Jordan, Our Last Best Chance: The Pursuit of Peace in a Time of Peril, New York: Viking, 2011, pp. 243-45

12. W. Andrew Terrill, Global Security Watch Jordan, Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2010, Chapter 6.

13. Christopher Dickey, “How the Arab Spring Has Weakened U.S. Intelligence,” Newsweek, June 20, 2011.

14. Arab politicians and commentators often applied the word “republic” to virtually all post-monarchical systems of government in the Arab World regardless of whether they hold free elections or not.

15. “Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement of The Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Republic: Report By the Director General,” International Atomic Energy Agency Board of Governors, February 20, 2004; and Gordan Corera, Shopping for Bombs, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006, Chapter 8.

16. Alawites are a minority Islamic sect in Syria. They are believed to comprise between 8-10 per cent of the population.

17. Note reference to these actions in President Obama’s speech, Office of the White House Press Secretary, “Remarks by the President on the Middle East and North Africa,” May 19, 2011, www.whitehouse.gov. Also see “Tehran accuses West of meddling in Syria,” Kuwait Times, June 15, 2011.

18. “Syria: Army, Police Officers defect, cross into Turkey,” Los Angeles Times, June 16, 2011.

19. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2010, London: IISS, 2011, p. 272.

20. This evaluation was contested at the time although the subsequent use of cluster munitions and multiple rocket launchers against civilians in Misrata seems to have removed quite a bit of doubt. Human Rights Watch, “Libya: Indiscriminate Attacks Kill Civilians,” April 17, 2011, www.hrw.org; “Gadhafi forces shell Misrata neighborhood,” United Press International, June 15, 2011.

21. “Libya rebels win $ 1.4b aid: UAE,” Khaleej Times, June 10, 2011; “Jordan, Qatar coordinate positions on common challenges, talk bilateral ties,” Jordan Times, April 20, 2011,

22. David Ignatius, “A Libyan Settlement?” Washington Post, June 15, 2011, p. 19.

23. Portia Walker, “Qatar Gets Libyan Opposition into Shape,” Washington Post, May 13, 2011; Doyle McManus, “Breaking Point in Libya,” Los Angeles Times, April 24, 2011.

24. Christopher Boucek, “Dangerous Fallout from Libya’s Implosion,” Carnegie Europe, March 9, 2011.

25. “Yemen arrests 29 al Qaeda suspects after raids,” Reuters, December 29, 2009.

26. Eric Schmitt and Scott Shane, “Saudis Warned U.S. of Attack Before Parcel Bomb Plot,” New York Times, November 5, 2010.

27. “Obama’s other surge—in Yemen,” Christian Science Monitor, August 25, 2010.

28. “Fighting Turns southern Yemen into ’hell’,” Khaleej Times, May 9, 2011.

29. “President Saleh will not return to Yemen: Saudi official,” Khaleej Times, June 17, 2011.

30. The Fiver Shi’ism embraced by the Houthis is usually considered particularly moderate and tolerant that is unreceptive to Iranian-style Shi’ite activism.

31. Maggie Michael, “Poll: Less than 1% of Egyptians favor Iran-style Islamic Theocracy,” Washington Times, June 5, 2011.

32. Scott Peterson, “Iran’s Khamenei praises Egyptian protesters declares ‘Islamic Awakening,,” Christian Science Monitor, February 4, 2011.

*****

The views expressed in this brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

*****

More information on the Strategic Studies Institute’s programs may be found on the Institute’s homepage at www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil.