Colonel John C. Valledor

We can find plenty to read and study on the subject of leadership; in fact, there is a veritable mountain of studies, essays, and books explaining how to build leaders. Not so if one wants to build (or become) a strategist.

General John Galvin1

Emerging Realities and the Education of Strategists.

Since the horrific attacks against the U.S. homeland on September 11, 2001 (9/11), the U.S. has been engaged in two very long and costly wars, with the war in Afghanistan formally ending on December 2014. At the heart of the grand strategy supporting these conflicts was the desire to deny failing and failed states from becoming the launch pad for future attacks. The closest the nation came to a grand strategy—known for years by its now familiar alias—“The Global War on Terror”2—served to focus U.S. military efforts and galvanize popular support for a common strategic cause.

The use of U.S. military force against certain countries in the greater Middle East has done much to eliminate terror-training camps and prevent al-Qaeda from launching large-scale follow-on attacks against the homeland. Nevertheless, U.S. military engagements overseas have unleashed many unforeseen consequences that have complicated the ability to achieve policy objectives.

The United States conducted a successful campaign to decapitate al-Qaeda and destroy its ranks. Still, there remained splinter groups rooted in Saudi Arabia’s extremist Salafist ideology of Wahhabism that have metastasized and spread their violent strand of Islam across the globe.3 Hijacked jetliners are no longer the weapon of choice. Instead, a new normal is emerging where self-radicalized, sociopathic Muslim gunmen are increasingly perpetrating the slaughter of innocent civilians through heinous commando-style killing sprees against Western nations and their citizens. In places like Fort Hood, TX; Mumbai, India; Boston, MA; Ottawa, Canada; Sydney, Australia; and Paris, France, these homegrown nihilistic militants murdered scores of civilians and leveraged the ubiquity of the Internet as the preferred medium for spreading an increasingly sophisticated propaganda and misinformation campaign. Their Salafist-jihadist message is that no one and no place is beyond their reach. Therefore, to borrow from Henry Mintzberg’s theory on “emergent strategy,”4 there is a need to educate today’s strategists to contend with the fact that our “deliberate strategy” after 9/11, has largely failed. This has resulted in a dire need to adapt to the changing realities that have followed.

Sadly, Islamists have undermined or coopted the Arab Spring movements that emerged in North Africa and the Middle East with much promise. In some cases, the result has been the collapse of secular Arab states that once served U.S. national interests. One by one, Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Syria, Yemen, a large swath of the African continent, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Levant have been transformed, some approaching a state of dystopia. Further, these states have become the breeding grounds for new waves of radical jihadists militants, some even more lethal than al-Qaeda. The rise of affiliated groups that operate at the nexus of criminality and terrorism, such as the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant, Boko Haram, and Al-Shabaab represent current manifestations of this emerging reality.

Given the turbulent security environment, the need for the U.S. military to develop leaders competent at strategic thinking is greater than ever. Accordingly, the U.S. Army War College (USAWC) hosted a Strategy Education Conference on September 22-24, 2014, in Carlisle, PA, to consider this need. Twenty-two organizations from across the U.S. Army’s professional military education (PME) enterprise—all stakeholders in the education of strategy—attended the conference. Electing to call themselves the Strategy Education Community of Interest (SE CoI), conferees focused their analytical efforts on addressing the question posed by the USAWC Commandant: How do we enable distributed education of strategy across the Army education enterprise while assuring coherency in the fundamentals of strategy?

The purpose of this article is to describe the methodology applied by the conferees and to share their insights. It aims to generate discourse across a broad audience of Army leaders who feel strongly that the Army, as a learning institution, can better educate the next generation of strategic thinking warfighters to successfully conduct sustained unified land operations and win in a complex world.

Interwar Years—Back to the Future.

In 1988, General John Galvin, former Supreme Allied Commander Europe, began his testimony before the House Armed Services Committee with a simple, yet powerful statement—“We need strategists.”5 General Galvin, one of many reformers of his generation, sought to change the culture within the U.S. Army. His comments underscored a key lesson learned from the complex period between 1973 and 1988 when the nation distanced itself from the Vietnam era and prepared for the culmination of the Cold War. His testimony included recommendations on how the Army could improve the way it selects, educates, and presents broadening experiences to future strategists. In retrospect, the effort to develop strategic thinkers who could formulate and persuasively argue coherent strategic options was mixed at best.

Today, we again find ourselves in yet another complex and chaotic period defined by an increase in the velocity and momentum of human interaction and events. In the greater Middle East, U.S. policy objectives are pitted against those of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria and by an Iranian theocracy with aspirations of becoming the world’s only nuclear Shia state. In the Eurasian landmass, Russia's illegal annexation of Crimea and increasingly provocative subversion and military maneuvers elsewhere in or bordering Ukraine serve notice of a resurgent and bellicose Russia. Along the western Pacific rim, China presses for regional hegemony, while a petulant North Korea demands our attention, given its possession of chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and high-yield explosive weapons and the attributable use of malicious cyber activity against Sony—a private American corporation. In Africa’s conflict-affected states, the combined effects of climate change, expanding Islamic minorities and pandemic diseases such as Ebola and HIV threaten to unravel the fabric of society. In the Western Hemisphere, transnational organized crime, international human trafficking rings, and weak governance threaten our national security as surely as any conventional adversary does.6

What is our response to the diversity of threats to U.S. security and vital interests? In today’s hyper partisan political and media environment, seemingly not a week goes by when Americans are not subject to the wholesale public bashing of our “National Strategy” (or the lack thereof). A seemingly ill-defined and vacillating national interest concerning these emerging security challenges is exploited not only by our adversaries, but also by savvy politicians, media pundits, and even some retired senior military officials. Our national security strategy has become a convenient piñata ripe for partisan acrimony. In the opinion of one MSNBC foreign policy analyst in today’s multi-platform media ecosystem, Rula Jebreal, ”ignorance is reigning supreme; ideology is becoming mainstream.”7 Interestingly, President Barack Obama’s release of the 2015 “National Security Strategy” has done little to quell acrimonious debate.8

According to a recent USA Today/Pew Research Center Poll, 54 percent of Americans are dissatisfied with what we are doing to address these emerging national security issues.9 After years of retrenchment and two costly wars, the desire for having complementary and coherent national strategies to address emerging threats is one area that is agreed upon by citizens across the political spectrum. All this implicitly points to a U.S. Government policymaking apparatus that appears to be struggling with crafting effective strategy and policy. To be fair, military trained and educated strategists and planners contribute to U.S. policymaking and therefore share some of the blame for its shortfalls.

A common misperception is that the formulation of national security strategy is a linear process whereby civilian policymakers set clear strategic objectives and U.S. military leaders craft supporting strategies to achieve them. In practice, the strategy making process is not nearly so well-defined. It is often messy and unstructured, with the responsibilities and interests of civilian and military leaders overlapping considerably. The shortcomings of the strategy making process have corresponding negative effects on the U.S. efforts to achieve its policy objectives.

A recently published study by the RAND Corporation posits that, after 13 years of war, “the making of national security strategy has suffered from a lack of understanding and application of strategic art.”10 Despite some recent improvements, “a wider appreciation of the degree to which this deficit produces suboptimal national security outcomes may be lacking.”11 More damning still to those in the profession of arms is the study’s finding that the formal strategy making process framed in U.S. military doctrine and taught in professional military education does not reflect current realities.12 Can military education do better? Yes. In the words of one prominent theorist on strategy and politics, Colin Gray, “People cannot be trained to be strategists, but they can certainly be educated so as to improve their prospects of functioning adequately or better in the strategic role.”13

The weakness in strategy education evokes Galvin’s call for developing strategic-thinking leaders and finding better ways to select, educate and assign them. Similarly, his suggestions to remedy the failings in strategy making are echoed in the RAND study that lists specific recommendations, including one whereby U.S. strategic competence could be enhanced by educating civilian policymakers and revising how policy and strategy are taught to the U.S. military.14

Criticism of the military’s weakness in formulating coherent strategy is not limited to think tanks like RAND. Increasingly, narratives from senior leaders once charged with formulating and executing our strategies in Iraq and Afghanistan are beginning to emerge. These narratives posit the poor exercise of “generalship” and the failure of generals charged with providing sound military advice to top civilian officials seeking the pursuit of strategic aims through war. In his recent book, Why We Lost, retired three-star general Dan Bolger offers one of many charges: “For soldiers, strategy, and operational art translate to ‘the big picture’ (your goal) and ‘the plan’ (how to get there). We got both wrong.”15 Others cut to the bone in their criticisms. In his essay, The Tragedy of the American Military, James Fallows posits that in spite of, “[our military] being the best-equipped fighting force in history . . . this force has been defeated by less modern, worse-equipped, barely funded forces. The U.S. military failed to achieve any of its strategic goals in Iraq.”16

Given the emergence of such sobering insights, it is appropriate that the U.S. Army in general, and its Senior Service College in particular, take the initiative in leading a team-of-teams effort to determine if the Army’s education enterprise is doing all it can to assure coherency in the education of strategy at all levels of the national defense continuum. After all, when it comes to the topic of strategy, the USAWC lists as a key objective to: “Serve as the de facto center for strategic thought for the Army, an immediately responsive resource for the thoughtful research and expertise in the strategic art of war.”17

Forming the Community of Interest.

In an effort to be inclusive of all relevant stakeholders having an interest in defining roles and requirements for strategists across the general purpose force and for educating current and future leaders from pre-commissioning to post-Senior Service College, the USAWC focused on establishing an atmosphere of collegiality. Leveraging subject matter experts across the Army, as well as resident faculty and staff, the War College led an effort to define and analyze how our education enterprise endeavors to train and educate future leaders on the subject of strategy.

The SE CoI included senior representatives of the Army, especially the G-35 directorate, given that this office is charged with establishing and sourcing the Army’s global requirements for strategists. Requirements across the Total Force, including the National Guard and Army Reserve, necessitated representation from those organizations. Those organizations charged with developing the pedagogy of strategy from pre-commissioning sources like the U.S. Military Academy and the education of officers at the midpoint of their careers sought the insights from senior educators at the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, KS, including faculty from the School of Advanced Military Studies. To address the education of officers at the Senior Service College level, senior faculty leads from the across the college, institutes, and centers within the USAWC campus, and the Basic Strategic Art Program course in particular, were included to share their program of record for the education of strategy. Finally, a senior research psychologist from the Army Research Institute (ARI) provided insight on an ongoing Army-wide study on strategic thinking competencies and associated enablers.

In concert with the Commandant’s opening question to conferees, the focus of the SE CoI was to produce and address the following as conference deliverables:

- Agree on a U.S. Army definition of “Strategy.”18

- Agree on a foundational strategy education framework.

- Share best practices among the SE CoI.

- Issue a post conference report highlighting key findings and addressing the way ahead.

- Publish a staffed conference report and follow-on journal article on the conference findings.

Conference Methodology.

The word ‘strategy’ has acquired a universality which has robbed it of meaning, and left it only with banalities.

Prof. Hew Strachan19

On September 23, 2014, conferees provided a series of information briefings highlighting their organizations’ role in the education of strategy across the SE CoI. The conferees then formed a single working group focused on establishing consensus and agreement on a key deliverable—a proposal for the Army’s definition of “strategy.” Using a series of historical examples provided as context, including the current Joint definition of strategy,20 conferees seemed to coalesce on one historical example in particular. The esteemed military theorist Sir B. H. Liddell Hart defined strategy as: “The art of distributing and applying military means to fulfill the ends of policy.”21 In an atmosphere of spirited discourse, the group blended, matched, and reconstructed several elements from other examples into a list of five prototypes until they subsequently reached consensus on three draft definitions. One definition, conceptual in nature, was constructed as the baseline for two other nested prototypes that followed. This generic definition would apply to any organization, not just the military. Special emphasis was made on designing a conceptual base definition that would, exhibit simple elegance.

Two follow-on strategy definitions were then constructed, with a focus on the national and military domains, respectively. Overall, the central theme of the group’s discussion was that strategy does not exist in a vacuum, and is primarily concerned with supporting a higher goal. Thus, the proposed national and military definitions make a distinction between the ends of strategy in pursuit of a higher-level policy objective. The group also considered the notion of power as an element in the proposed definitions, but eventually returned to the familiar ends-ways-means paradigm.

Additionally, the group discussed the importance of “context” and thus the subsequent identification of various educational modules that build the foundation for strategic thinking. These definitions were then set aside for conferees to reflect on for reconsideration later.

The conferees were divided into parallel brainstorming work groups. Work was informed by the research findings from the ARI, specifically the strategic thinking competencies and enablers.22 The strategic thinking competencies and enablers were developed from a review of academic, military, and business literature and interviews with Division level commanders, Division level staff, civilian advisors, and PME instructors (55 participants total, including 15 general officers). The ARI distinguishes between strategic thinking competencies that are required for the cognitive process of strategic thinking (e.g., critical thinking), and strategic thinking enablers that either contribute to the strategic thinking process (e.g., broad knowledge) or help translate strategic thinking to others (e.g., communication). Likewise, a separate group was formed to create a graphic representation of the strategy education framework that looked at the enterprise built around the cognitive objectives of Bloom’s taxonomy,23 the PME hierarchy, and the three leader development pillars: training, education, and experience. The goal was to blend the best elements of both group renderings into one construct in both text and graphic format.

On September 24, 2014, conferees reconvened and continued to refine their group renderings prior to a mid-morning series of out briefings. By mid-morning, the conferees subsequently reached consensus as a group (with some participants not in agreement) on three draft definitions of strategy and one final rendering depicting a proposed strategy education framework with an associated matrix highlighting competencies and enablers that underpin the U.S. Army PME enterprise.

Conference Outcomes.

The SE CoI tentatively achieved consensus on the following definitions:

- Strategy. The alignment of ends, ways, and means—informed by risk—to attain goals.24

- National Strategy. The alignment of ends, ways, and means to attain national policy objectives.

- Military Strategy. The art and science of aligning military ends, ways, and means to support national policy objectives.

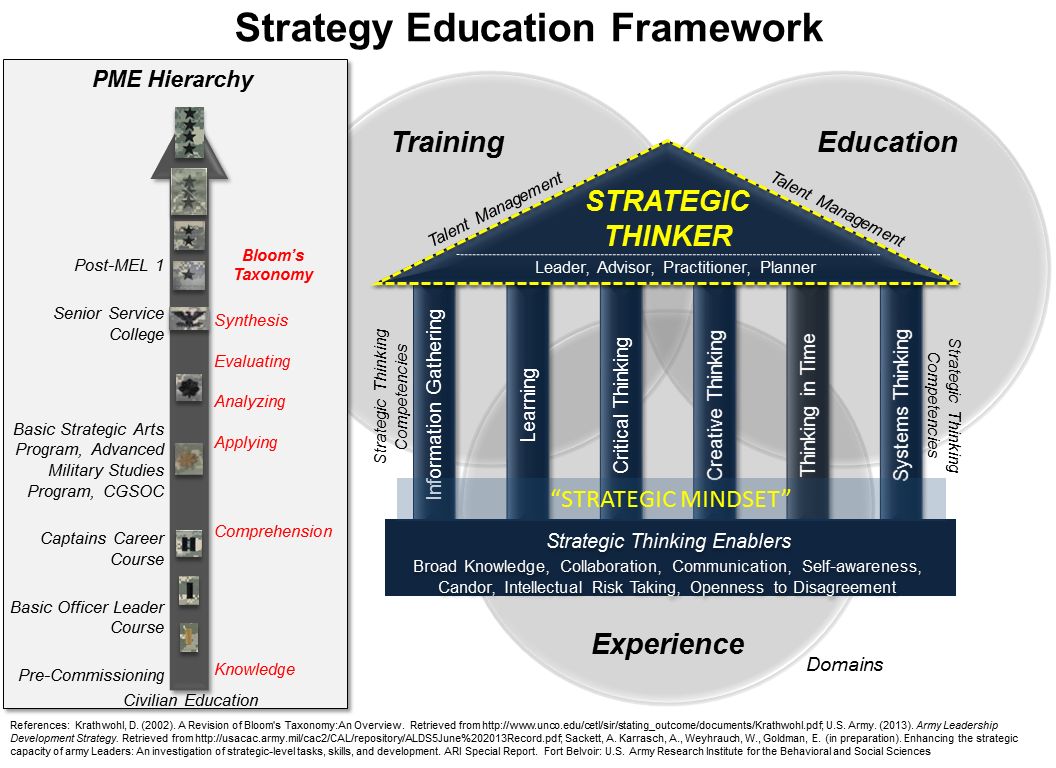

In addition to defining strategy, the SE CoI developed a proposal for a strategy education framework. The conferees used the metaphor of a Greek temple, a readily identifiable graphic modeled after the U.S. Army Leader Development Strategy (see Figure 1) to illustrate this framework.

Figure 1. Strategy Education Framework.

The base of this framework represents strategic thinking enablers: broad knowledge, communication, collaboration, self-awareness, and risk taking—that are foundational for all officers regardless of position or rank. Pillars that buttress this framework include the strategic thinking competencies derived from ARI’s research—Learning, Information Gathering, Systems Thinking, Creative Thinking, Critical Thinking, and Thinking in Time. These competencies and enablers create a “strategic mindset” along an officer’s educational path and are integrated throughout the delivery of PME courses at varying levels of learning per Bloom’s taxonomy.25

The diagram is illustrative of the PME hierarchy for strategy education and its associated cognitive learning objectives. This is consistent with Bloom’s taxonomy described in the Officer Professional Military Education Policy (OPMEP). Rigorous curricula in strategy and strategic thinking from pre-commissioning thru post-Military Educational Level 1 (MEL 1) courses, along with the strategic thinking competencies, combine to grow a strategic thinker over time. Learning at the higher levels of the PME hierarchy depends on the individual officer having attained prerequisite knowledge and skills in the subject of strategy at the lower levels.

The apex of the Greek temple graphic depicts the Army’s strategy education continuum objective—the creation of strategic thinkers who successfully imbue the strategic thinking competencies and complete strategy-focused curricula along the PME hierarchy. Most importantly, the pool of strategic thinkers at the top is not just limited to general officers. Rather, it includes roles that officers perform in the capacity of senior leaders themselves, as advisors to senior strategy and policymakers, practitioners of strategy formulation, and strategic planners. Further, the Army's personnel management system must address this same pool of strategic thinkers through a talent management system that identifies leaders who think strategically and place them in positions of senior leadership.

Finally, the conferees recognized that learning is not limited to education. Training and experience along an officer’s career path are equally important to the creation of strategic thinkers. Thus, the education domain will contain courses at each PME level that support strategy education, while the training and experience domains will contain activities, assignments, or other areas of concentration that also support strategy education.

Given the limitations of time in a 1 1/2-day conference, the SE CoI acknowledged the need to further explore and refine the strategic thinking competencies and enablers at a future conference. The next step is for the education provider to refine the outcomes, indicators, and required assessment models for the competencies and enablers identified. The final product of this follow-on effort will be brought back to the SE CoI forum for further analysis and to identify gaps and redundancies.

Alternative Approaches to Defining “Strategy”—the Accordion Word.

Could the SE CoI have applied an alternative approach to derive an updated definition of strategy? Yes. The SE CoI in future work may benefit from referencing the following two authors who have done extensive work on this topic. Applying Sartori’s 12 guidelines methodology (outlined as follows) could result in the SE CoI’s refinement of the term “strategy.”

When it comes to tracing the etymology of strategy there is no better than Beatrice Heuser’s The Evolution of Strategy, Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present.26 Heuser applies an onomasiological approach defined in Merriam Webster’s dictionary as, “the study of words and expressions having similar or associated concepts and a basis,” tracing the history and evolution of the term strategy from Greek antiquity to modern day. This work should serve as a starting point for anyone charged with attempting to define its evolving meaning over time.

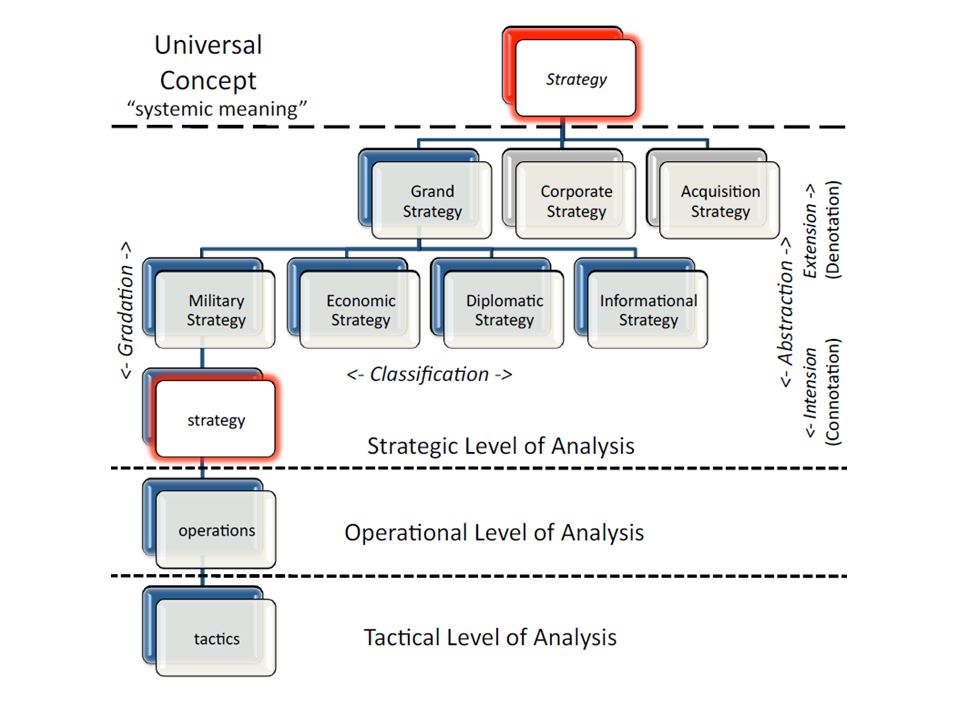

Randall Bowdish offers another approach to defining strategy in his Military Strategy: Theory and Concepts.27 He notes that political scientist Giovanni Sartori developed a methodology that includes “12 Guidelines for Concept Analysis.” Applying Sartori’s methodology, Bowdish crosswalks the elements of 19 different definitions of the term “strategy” from theorists Sun Tzu, Liddell Hart, Colin Gray, and Art Lykke, the favored source in the USAWC and others, to arrive at a generic version of the term. He then applies two rules from Sartori: (1) “Always check whether the key terms are used univocally and consistently in the declared meaning,” and, (2) “Awaiting contrary proof, no word should be used as a synonym for another word.” With these rules in mind, Bowdish defines strategy as, “A plan that describes how military means and concepts of employment are used to achieve military objectives.”28 Clearly, Bowdish’s use of the Sartori methodology reveals a definition of military strategy different from that determined by the SE CoI. Bowdish’s approach, depicted in Figure 2, is referenced here in anticipation of its consideration by the SE CoI at a future meeting.

Figure 2. Typology of Strategy.29

The Way Ahead.

Somewhere within the ranks of the U.S. Army, a second lieutenant is just beginning to navigate the echelons of command as part of his career road map. No doubt his successive assignments will build on his experiential base of knowledge and skills, one that began during pre-commissioning. Furthermore, his progression through the existing PME hierarchy will expose him to a broad set of topics deemed essential for the broadening of military professionals, including strategy. Finally, the officer’s increasing exposure to a host of superior, subordinate, and peer leaders—many with diverse backgrounds—will also add to his growing knowledge of leadership in positions of strategic impact. Leveraging what the Army Operating Concept calls “human performance optimization,” advances in science and technology will someday result in producing “young leaders with the experience, maturity and judgment previously expected of a more senior and experienced leader.”30 Decades from now, this officer could reach the apex of the career pyramid, assigned as a strategic leader, advisor, theorist, or planner. There is no better time than now to begin the process of developing a new generation of competent Army officers (as strategists) who are adept partners in the civil-military strategy-making enterprise. The military’s education of strategy and strategists must be capable of dealing with the emerging security challenges of the twenty-first century. As military professionals, we owe this to the nation we protect and the citizens who entrust their sons and daughters to our care.

ENDNOTES

1. John R. Galvin, “What’s the Matter with Being a Strategist?” Parameters, Vol. XIX, March 1989, p. 2, available from strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/parameters/Articles/1989/1989%20galvin.pdf.

2. Hew Strachan, The Direction of War: Contemporary Strategy in Historical Perspective, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, p. 11. The author asserts that the global war on terror “was a statement of policy; it was not a statement of strategy.” In fact, he later calls this confusion between strategy and policy, “strategically illiterate.”

3. Sawsan Ramahi, “The Muslim Brotherhood and Salafist Jihad (ISIS): Different Ideologies, Different Methodologies,” Middle East Monitor, September 29, 2014, available from https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/articles/middle-east/14418-the-muslim-brotherhood-and-salafist-jihad-isis-different-ideologies-different-methodologies.

4. Henry Mintzberg, The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning, New York: The Free Press, 1994, pp. 23-25.

5. Galvin, p. 2.

6. Department of the Army, Training and Doctrine Command Pamphlet (TRADOC) 525-3-1, Change 1, The U.S. Army Operating Concept: Win in a Complex World 2020-2040, Fort Eustis, VA: TRADOC, October 31, 2014, p. 14, available from www.tradoc.army.mil/tpubs/pams/TP525-3-1.pdf.

7. Elias Isquith, “Ignorance Is Reigning Supreme,” Rula Jebreal on “Charlie Hebdo, Bill Maher & Our Insane Foreign Policy,” Salon, January 16, 2015, available from www.salon.com/2015/01/16/ignorance_is_reigning_supreme_rula_jebreal_

on_charlie_hebdo_bill_maher_our_inane_foreign_policy/.

8. The White House, National Security Strategy, 2015, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, February 2015, available from www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/2015_national_security_strategy_2.pdf.

9. Susan Page, “Poll: Amid Foreign Crisis, More Americans Support U.S. Action,” USA Today, August 26, 2014, available from www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2014/08/28/usa-today-pew-poll-us-role-in-the-world/14623319/.

10. Linda Robinson, Paul D. Miller, John Gordon IV, Jeffrey Decker, Michael Schwille, and Raphael S. Cohen, “Improving Strategic Confidence, Lessons from 13 Years of War,” Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation Arroyo Center, 2014, p. 32, available from www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR800/RR816/RAND_RR816.pdf.

11. Ibid., p. 33.

12. Ibid., p. 34.

13. Colin S. Gray, The Strategy Bridge: Theory for Practice, New York: Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 155.

14. RAND, p. 105.

15. Daniel Bolger, Why We Lost, A General’s Account of the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars, New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing, 2014, p. 12.

16. James Fallows, “The Tragedy of the American Military,” The Atlantic, January/February 2015, p. 12, available from www.theatlantic.com/features/archive/2014/12/the-tragedy-of-the-american-military/383516/.

17. Strategic Plan “Strategy Map,” U.S. Army War College, Carlisle Barracks Online, 2015, available from internal.carlisle.army.mil/sites/G3/Shared%20Documents/Strategy%20Map/STRATEGY%20MAP18%20Dec%202014.pdf.

18. Interestingly for reference, the U.S. Marine Corps broadly defines strategy as “the process of interrelating ends and means. When applied to a particular set of ends and means, the product—that is, the strategy—is a specific way of using specified means to achieve distinct ends.” U.S. Department of the Navy, Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1-1, Strategy, Washington, DC: Headquarters, United States Marine Corps, November 12, 1997, p. 37, available from www.marines.mil/Portals/59/Publications/MCDP%201-1%20Strategy.pdf.

19. Strachan, p. 27. The author argues that strategy confronts an existential crisis: it should never be used as a synonym for policy. By confusing strategy with policy, governments denied themselves the intellectual tool to manage war for political purpose.

20. Joint Publication 1-02, Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, defines strategy as: “A prudent idea or set of ideas for employing the instruments of national power in a synchronized and integrated fashion to achieve theater, national, and/or multinational objectives (JP 3-0),” November 8, 2010, as amended August 15, 2014, p. 242, available from www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp1_02.pdf.

21. Basil H. Liddell Hart, Thoughts on War, London, UK: Faber & Faber, 1944, p. 229.

22. A. Sackett, A. Karrasch, W. Weyhrauch, and E. Goldman, “Enhancing the Strategic Capacity of Army Leaders: An Investigation of Strategic-Level Tasks, Skills, and Development,” ARI Special Report, Fort Belvoir, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, forthcoming.

23. B. S. Bloom, Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals, Austin, TX: Susan Fauer Company, Inc., 1956, pp. 201-207. Original categories included Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation.

24. The U.S. Army War College definition of strategy was adopted by the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) in a recent "Force 2025" information briefing to a panel of general officers, February 27, 2015.

25. Ibid.

26. Beatrice Heuser, The Evolution of Strategy, Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010, pp. 3-29.

27. Randall G. Bowdish, Military Strategy: Theory and Concepts, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska, June 2013, pp. 268-288, available from digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1026&context=poliscitheses.

28. Ibid., pp. 273-286.

29. Ibid., p. 284.

30. TRADOC Pamphlet 525-3-1, p. 39.

*****

The views expressed in this Strategic Insights article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This article is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited.

*****

Organizations interested in reprinting this or other SSI and USAWC Press articles should contact the Editor for Production via e-mail at SSI_Publishing@conus.army.mil. All organizations granted this right must include the following statement: “Reprinted with permission of the Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press, U.S. Army War College.