Introduction

As one of the three branches of China’s armed forces, the People’s Armed Police (PAP) (人民武装警察) operates alongside the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) (人民解放军) and the militia (民兵) as a key instrument of Chinese Communist Party power. According to the Science of Military Strategy, a foundational textbook used to educate senior Chinese military officers, the People’s Armed Police is tasked with meeting the strategic requirements of “multi-functional integration, stability and rights maintenance” (多能一体,维稳维权).1 With a force exceeding 500,000 personnel, the People’s Armed Police is structured into specialized components, including the Internal Security Force, mobile contingents (机动总队), and the China Coast Guard.2 This varied force structure, distinct from any service in the US military, enables the People’s Armed Police to execute a broad range of missions, from domestic stability to supporting PLA operations.

The PAP institutional design places the People’s Armed Police in stark contrast to militarized police forces worldwide because the force answers solely to China’s top military authority. Unlike Italy’s Carabinieri, which operates under both the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Interior, the People’s Armed Police falls entirely within the military chain of command. Previously subject to a dual-command system shared with China’s State Council, the People’s Armed Police was placed fully under Central Military Commission control in 2018. This shift removed all civilian oversight at local and provincial levels, reinforcing the PAP role as a centralized military entity rather than a law enforcement organization. This distinction is further underscored by the frequent movement of officers between the People’s Armed Police and the People’s Liberation Army, a level of integration uncommon among military police forces elsewhere. Most notably, Central Military Commission member Liu Zhenli previously served as the People’s Armed Police’s chief of staff before assuming the same role in the PLA Army.

According to a military textbook used in Tsinghua University’s national defense curriculum, the PAP Internal Security Force operates under regional commands aligned with China’s provinces, autonomous regions, and major cities.3 These units perform fixed-site security missions, urban armed patrols, and rapid-response duties aimed at maintaining domestic stability. Internal Security Force units are also responsible for securing critical infrastructure and responding to emergencies, including natural disasters.

The PAP provincial-level units, known as zongdui (总队), form the backbone of the People’s Armed Police’s internal-security operations. Each of China’s 31 provincial-level administrative regions hosts a zongdui; Xinjiang houses two because the extra unit supports the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps. These zongdui are further divided into duty zhidui (执勤支队), responsible for local guard duties and patrols, and mobile zhidui (机动支队), which provide rapid-response capabilities based on regional security conditions. The Beijing zongdui, the largest in the People’s Armed Police, consists of 14 duty zhidui and four mobile zhidui. Beneath the zhidui level, units are structured into dadui (大队), roughly equivalent to battalions, and zhongdui (中队), which align with company-sized formations.

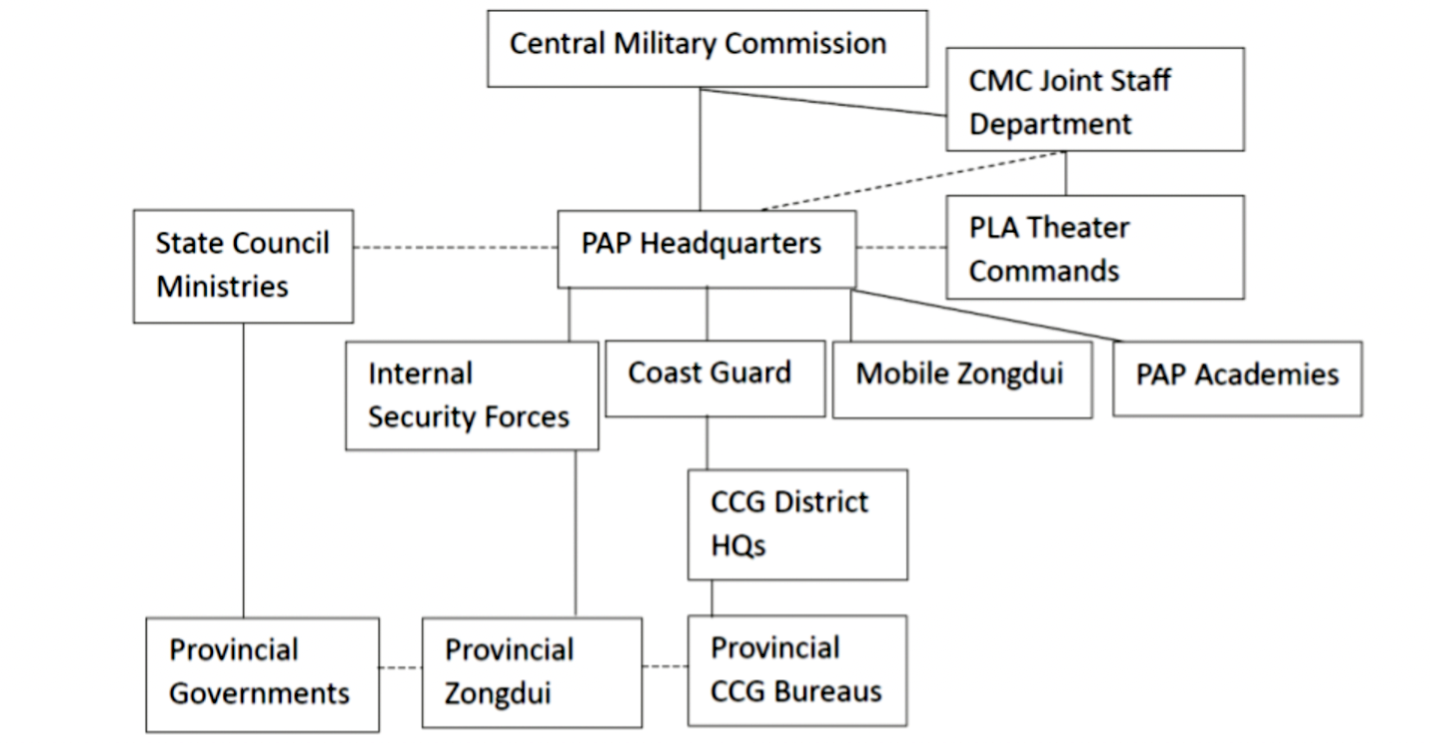

Figure 1. Organization of the PAP

(Source: Graphic created by Joel Wuthnow. Used with his permission.)

In addition to the domestic-security role, every provincial zongdui maintains a counterterrorism capability through designated SOF units or tezhang dadui (特战大队). These specialized formations are tasked with handling high-risk operations like hostage rescues and armed interventions against terrorist threats. This tiered structure allows the People’s Armed Police to maintain a permanent local-security presence while ensuring rapid-deployment capabilities for contingencies that require armed force. At the national level, the People’s Armed Police serves as China’s primary counterterrorism force, with three elite units designated as national-level counterterrorism assault forces (国家级反恐突击力量): the Snow Leopard Commandos (雪豹突击队), Falcon Commandos (猎鹰突击队), and Mountain Eagle Commandos (山鹰突击队).

In parallel, the mobile contingents constitute a more agile, combat-capable component tasked with responding to large-scale domestic disturbances, conducting counterterrorism operations, and reinforcing internal-security forces when necessary. Structurally, the mobile contingents include two corps leader–grade formations that provide national and local leaders with additional rapid-response capabilities. Unlike the provincial contingents, these commands do not have a fixed geographic area of responsibility but can be deployed flexibly for crisis response. Although these contingents have designated headquarters, mobile contingent units are geographically dispersed, allowing them to conduct operations far beyond the units’ primary bases. For instance, elements stationed near Guangzhou participated in exercises in Shenzhen during the 2019 Hong Kong protests. The 1st Mobile Contingent, based in Shijiazhuang, is well positioned to reinforce PAP units in Beijing in the event of a crisis.4 The 2nd Mobile Contingent, headquartered in Fuzhou, could play a role in supporting PLA operations in a Taiwan Strait contingency. The two mobile contingents also contain the PAP helicopter and engineering units.

The capabilities and equipment of the People’s Armed Police are more indicative of a light-infantry military force rather than a paramilitary organization. Personnel, field, military-grade weapons and platforms—including Dongfeng CSK-181 light tactical vehicles, DZJ-08 (Type 08) rocket launchers, and self-propelled 82-millimeter mortars—are all far beyond the capabilities of a typical internal-security force.5 Modernization priorities outlined in the Science of Military Strategy emphasize enhancing PAP “troop transport, command, armored vehicles, lethal weapons, and engineering and chemical defense equipment” to enhance combat effectiveness.6 The Science of Military Strategy also aligns PAP development with broader PLA modernization efforts, stressing “informationization” and “intelligentization” to generate combat effectiveness and the advancement of “military-civil” fusion to accelerate the development of intelligent and unmanned combat forces.7

Figure 2. Soldier from the PAP fires vehicle-mounted mortar system

(Source: CCTV 7, “配置拉满!中国武警竟然用上炮了!车载速射迫击炮官宣入列 让武警火力直线提升!海量新装备展示作战模式 穿越机化身战场利器 歼敌于无声!” [Fully equipped! The People’s Armed Police actually used cannons! The vehicle-mounted rapid-fire mortar officially joins the force, enhancing firepower! A massive display of new equipment and combat modes, drones become battlefield weapons, defeating the enemy silently!] (军事纪实 [Junmi Tianxia], October 29, 2024), YouTube video https://www.youtube dot com/watch?v=DRP8BI1Bgv4.)

Defense journals from professional military educational institutions explicitly frame the People’s Armed Police as a force designed for warfighting. A study from the People’s Armed Police Command College highlights the necessity of “multi-service joint operations” (多军兵种联合作战) and “highly integrated operational forces” (作战力量高度合成) in future conflicts.8 The highest levels of China’s leadership reinforce this emphasis on operational integration. In January 2018, Xi Jinping directed the People’s Armed Police to enhance its “combat-ready training” and “speed up its integration with the People’s Liberation Army’s joint operation system.”9 More recently, Xi explicitly linked the People’s Armed Police to these goals when he urged the elite Falcon Commandos to “remain at the forefront of special operations, continually improving mechanisms for generating new combat capabilities.”10 Given the force’s growing operational flexibility, high mobility, and direct integration into China’s armed forces, the People’s Armed Police is a critical but often overlooked element of Chinese landpower that warrants closer examination for its potential roles in future conflicts.

Internal Security and Stability Operations

The People’s Armed Police first and foremost plays a central role in maintaining domestic stability within China, operating as the state’s primary force for internal security, large-scale riot control, counterterrorism, and the suppression of unrest in politically sensitive regions like Tibet and Xinjiang. According to the Science of Military Strategy, the People’s Armed Police “shoulders major responsibilities in maintaining national security, social stability and defending the people’s good lives. It has an important role in maintaining political security, especially regime security, and institutional security.”11 This mandate highlights the People’s Armed Police’s critical function as a force for both day-to-day security operations and crisis response in defense of the Chinese Communist Party.

Although China’s civilian police forces under the Ministry of Public Security handle routine law enforcement, they are neither structured nor equipped to manage large-scale unrest. When protests, riots, or other mass incidents exceed the capacity of local authorities, municipal or provincial leaders can escalate the response by requesting PAP intervention.12 Although it is not under the direct command of local governments, the People’s Armed Police routinely coordinates with provincial and municipal authorities, providing the necessary manpower to enforce stability operations. Rules of engagement for PAP support to civilian police are likely established at multiple levels, ensuring a structured framework for cooperation.

Given most Chinese police officers historically did not carry firearms, the People’s Armed Police has traditionally served as the country’s designated force for situations requiring armed intervention. During the 1990s and 2000s, PAP forces were frequently mobilized to suppress “mass incidents” (群体性事件), including labor strikes, land disputes, and environmental protests. In 2005, PAP units were deployed to Shanwei, Guangdong, where they used lethal force against demonstrators, resulting in at least 20 deaths.13 In the 2011 Wukan village protests, the People’s Armed Police was deployed to seal off the village and end the perceived rebellion.14 But as local law enforcement personnel have adopted armed patrols, the People’s Armed Police has potentially become less central to routine crowd control. This shift in local police capabilities might enable the People’s Armed Police to focus more on coordinating with the People’s Liberation Army in a rear-area support role.

The People’s Armed Police has also played a decisive role in suppressing dissent in Tibet and Xinjiang, regions of strategic and political sensitivity for the Chinese Communist Party. In 2008, when widespread protests erupted across Tibet, PAP units were mobilized to impose curfews, conduct mass arrests, and engage in urban pacification efforts.15 Later, in 2013, PAP forces responding to protests in Biru county reportedly beat, detained, and fired on unarmed Tibetan demonstrators.16 Following a series of high-profile attacks attributed to Uyghur militants, the People’s Armed Police expanded its counterterrorism footprint in Xinjiang. The concentration of PAP forces in northwestern China remains higher than in any other region, underscoring the force’s role in regime protection against perceived separatists.17 Through years of sustained operations in these restive regions, PAP units have engaged in some of the most intense and prolonged security operations of any Chinese armed force, making the units’ troops among the most experienced in the nation’s security apparatus.

As noted in Science of Military Strategy, the People’s Armed Police must “strive to achieve a flexible combination of force elements, an organic integration of force systems, and a high degree of integration of system effectiveness.”18 This evolution aligns with broader reforms that were designed to expand the People’s Armed Police’s operational reach, enhance PAP responsiveness, and extend the force’s role beyond domestic stability operations. As the force modernizes, its integration into joint operations and potential use in future conflicts warrant closer scrutiny.

Roles of the People’s Armed Police in a Conflict Scenario

In a future conflict contingency, the People’s Armed Police would play an important role in ensuring the Chinese Communist Party can wage war without domestic disruption; supporting the People’s Liberation Army in combat operations; and potentially, securing control in a post-conflict environment. Although often viewed as a domestic paramilitary force, the People’s Armed Police has demonstrated conventional military capabilities that can deploy beyond China’s borders, raising important implications for US and allied military planning in the Indo-Pacific. The force’s responsibilities span pre-conflict stabilization, wartime rear-area security, and perhaps even post-conflict pacification, making the People’s Armed Police a key enabler of China’s military operations.

Pre-Conflict Domestic-Stabilization Operations as Key Indicators and Warnings

The People’s Armed Police functions as a frontline force for domestic stability inside China, ensuring internal security before military operations and preempting unrest that could interfere with defense planning. This role could extend beyond riot suppression, encompassing control over critical infrastructure, telecommunications, and transportation networks.19 Therefore, large-scale PAP mobilization and the movement of PAP mobile contingents serve as potential indications and warnings of impending PLA military action.

China’s 2019 intervention in Hong Kong provides a clear precedent in this regard. In August 2019, thousands of PAP personnel were staged in Shenzhen. Satellite imagery confirmed the presence of armored vehicles, troop carriers, and large formations conducting drills across the border near Hong Kong.20 This force was subsequently used to suppress Hong Kong demonstrations.21 In a future conflict, PAP deployments would both reinforce domestic stability inside China and likely facilitate military mobilization by securing transportation hubs, restricting information flows, and suppressing early dissent. During a visit to the 2nd Mobile Contingent, Xi underscored the need for force pre-positioning (力量预置) to ensure the People’s Armed Police could rapidly respond to crises.22 This guidance on proactive deployment further suggests large-scale PAP movements, particularly in regions geographically proximate to Taiwan, such as Fujian, could serve as an early warning of imminent military action, providing the United States and its allies a critical window to prepare.

Rear Support to PLA Operations

Once a hypothetical conflict began, the People’s Armed Police would play a key role in securing rear areas—especially, traffic control along road and rail supply lines as well as other logistical tasks essential for sustaining PLA operations. The 2006 Science of Campaigns outlines PAP coordination with active and reserve PLA units and local governments for defensive operations (防卫作战), including anti-air assaults, counter-sabotage, and the maintenance of transportation networks.23 A 2012 article by Wang Shucheng and Xie Feng from the PAP Headquarters’ Training Department further highlighted the need for the People’s Armed Police to integrate its operations with both military and civilian elements to maintain stability and ensure operational effectiveness in rear areas.24 By 2020, the Science of Military Strategy had stated the People’s Armed Police “should be capable of rear defense, maintaining order, and supporting operations.”25 Together, these sources demonstrate the evolving PAP role in supporting PLA operations.

The People’s Armed Police’s logistics capabilities are institutionalized within the Logistics University of the People’s Armed Police Force, which provides training across logistics, transportation, and medical-support disciplines.26 The college’s curriculum thus closely aligns with the expected wartime rear-support responsibilities of the People’s Armed Police. The PAP role in China’s COVID-19 response further demonstrates the force’s ability to conduct large-scale logistics operations in coordination with the People’s Liberation Army. During the crisis, the People’s Armed Police worked under a joint command structure led by the Central Military Commission’s Logistics Support Department, managing transportation, medical logistics, and quarantine enforcement.27 The scale and complexity of this effort exhibit a capability directly applicable to wartime rear-area support operations. The People’s Armed Police also maintains training facilities for rear-area defense operations where personnel engage in scenario-based training to refine their ability to secure critical infrastructure, manage supply lines, and coordinate battlefield support.28 These efforts highlight the PAP role in ensuring both stability and sustainment of PLA operations in a wartime environment.

Pacification and Post-Conflict Stabilization

Should the People’s Liberation Army achieve military success in Taiwan, the People’s Armed Police could also be tasked with post-conflict stabilization. Although this role remains speculative, PAP expeditionary activities and military writings serve as evidence of potential involvement. The People’s Armed Police has increasingly engaged in deployments beyond China’s borders. The 2015 Counterterrorism Law of the People’s Republic of China explicitly authorizes the People’s Armed Police to conduct overseas operations, and PAP forces have been airlifted to Russia for joint counterterrorism drills, demonstrating long-range deployment capability.29 A 2023 PAP mobility exercise demonstrated the use of rail, highway, and maritime transportation to deploy, reflecting a novel and advanced approach to operational flexibility.30 The People’s Armed Police has also conducted island combat (岛上作战) exercises in which special operations units practiced amphibious landings, reconnaissance, and key terrain security.31 Maritime counterterrorism training further enhances the force’s ability to operate in littoral and riverine environments, and helicopter-insertion exercises reinforce rapid-reaction and mobility capabilities.32 These developments demonstrate the People’s Armed Police provide more than just domestic security, positioning the force as a potential enforcer of political stability in territories beyond the Chinese mainland.

The People’s Armed Police’s overseas presence is not limited to training exercises. A permanent PAP base in Tajikistan, near the Afghan and Chinese borders, offers valuable experience in sustained out-of-area operations.33 Satellite imagery indicates a facility capable of housing a battalion-sized force with armored-support and rotary-wing assets.34 Rotations in and out of the base could hone PAP logistics and command structures for extended deployments. The Tajikistani base thus provides a test bed for the evolving PAP mission set.

Worth reemphasizing is PAP forces bring operational experience the People’s Liberation Army largely lacks. Units assigned to Xinjiang and Tibet have been engaged in counterinsurgency and internal-security operations for years, providing practical experience in population-control measures. Hence, these forces would be well positioned to conduct stabilization missions in occupied territory on Taiwan, particularly if PLA ground forces remain focused on any ongoing conventional operations. Given the strategic proximity to Taiwan, particular attention must be focused on the 2nd Mobile Contingent, stationed in Fuzhou. During a 2021 inspection by Xi, the contingent demonstrated its capabilities across various specialized training areas, including counter-explosives, chemical reconnaissance, engineering operations, and bridge construction.35 Continuous tracking of the 2nd Mobile Contingent’s readiness and training is essential to understanding the role the contingent may play in any post-conflict stabilization efforts.

Overall, the extent of the PAP role in a campaign to pacify Taiwan remains uncertain. Kevin McCauley notes, “Provisions for civilian control and reconstruction [of Taiwan], supported by the employment of People’s Armed Police national-level units, would need careful advanced planning.”36 Nevertheless, PAP expeditionary capability and operational experience suggest the People’s Armed Police could be a key element of China’s strategy for consolidating control over Taiwan. Monitoring PAP training, deployments, and coordination with PLA forces will be essential in developing a comprehensive picture of China’s preparedness for such a scenario.

Conclusion

The People’s Armed Police is a critical component of China’s armed forces with expanding responsibilities that warrant sustained monitoring. From an indication-and-warning perspective, the movement of PAP forces—particularly, mobile contingents—should be closely tracked because their deployment often signals imminent security operations.

The People’s Armed Police’s exercises provide further insight into the evolving role of these forces in operational sustainment and rear-area security for the People’s Liberation Army. Although PAP forces are positioned to play a role in logistics, force protection, and internal stability during a conflict, the precise extent of the forces’ notional coordination with PLA operations remains unclear. Exercise patterns, including those used in joint training with PLA units and the scale and focus of logistics drills, offer valuable indicators of the intended function of PAP forces in a wartime environment.

Beyond domestic operations, the expeditionary capabilities of the People’s Armed Police warrant close attention. Participation in overseas exercises and missions as well as the lift assets used for PAP deployment signal an ability to project power beyond China’s borders. This capability has direct implications for a Taiwan contingency, in which the Central Military Commission could task PAP forces with pacification operations. Additionally, examining PAP responses to mass incidents inside China may provide insight into how the force would manage noncombatants in wartime.

Despite its expanding capabilities and mission set, the People’s Armed Police continues to face operational and structural challenges. The increasing scale and complexity of domestic mass incidents have placed greater demands on force coordination and crisis response.37 Internal assessments highlight persistent weaknesses in early warning, command integration, and logistical support. At the same time, an analyst at the People’s Armed Police Command College acknowledges limitations in PAP equipment and technological capabilities.38 Notably, Zhang emphasizes the need to import foreign technology to bridge gaps in digitization, networking, and command systems—developments that should be monitored closely to prevent inadvertent US or allied contributions to PAP modernization.

Ultimately, the People’s Armed Police is a critical and evolving element of Chinese landpower. The PAP role in internal security and operational sustainment is expanding, with direct implications for regional stability and US defense planning. Understanding the force’s trajectory will be essential in anticipating China’s ability to project coercive power and manage security challenges in future conflict contingencies.

Jake Rinaldi

Dr. Jake Rinaldi is a defense analyst at the China Landpower Studies Center within the Strategic Studies Institute at the US Army War College. Rinaldi holds a PhD and a master of philosophy degree from the University of Cambridge, where his doctoral dissertation examined Sino-North Korean military relations and his master’s degree focused on China’s nuclear forces.

Acknowledgments: The author is grateful to Colonel Nicola Mangialavori of the Carabinieri for generously sharing his time and insights on gendarmerie forces, which significantly enriched the perspective of this article.

Endnotes

- Xiao Tianliang 肖天亮, ed., 战略学 [Science of Military Strategy] (People’s Liberation Army [PLA] National Defense University Press, 2020), 423; and Xiao Tianliang 肖天亮, ed., Science of Military Strategy 2020, trans. China Aerospace Studies Institute (China Aerospace Studies Institute, 2022). Note: The term “rights maintenance” [维权] in Chinese strategic discourse refers to the defense of state sovereignty and territorial claims, including maritime rights protection in disputed areas, such as the South China Sea. Unless otherwise noted, English-language quotations refer to the China Aerospace Studies Institute’s translation of Science of Military Strategy. Return to text.

- The People’s Republic of China has not officially disclosed the size of the People’s Armed Police since the 2015–16 reforms. See Office of the Secretary of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2024 (Department of Defense, 2024), 75. Return to text.

- Liu Wenbing 刘文炳, ed., 军事课教程 [Military course textbook] (Tsinghua University Press, 2020), 37–39. Return to text.

- Joel Wuthnow, China’s Other Army: The People’s Armed Police in an Era of Reform, China Strategic Perspectives no. 14 (National Defense University Press, 2019), 13. Return to text.

- “东风猛士新型车型 首次列装武警部队” [DFM’s new model of Dongfeng Mengshi enters service with the Armed Police], Dongfeng Motor Corp Daily, June 19, 2020, https://www.dfmc.com.cn/news/company/news_20200619_1011.html; Li Yufeng 李雨峰 and Zhou Jing 周静, “硬核来袭!直击武警官兵迫击炮实弹射击现场” [Hardcore attack! On-site coverage of the People’s Armed Police mortar live-fire exercise], PLA Daily, September 15, 2021, http://www.81.cn/pk/10089548.html; and CCTV 7, 配置拉满!中国武警竟然用上炮了!车载速射迫击炮官宣入列 让武警火力直线提升!海量新装备展示作战模式 穿越机化身战场利器 歼敌于无声! [Fully equipped! The People’s Armed Police actually used cannons! The vehicle-mounted rapid-fire mortar officially joins the force, enhancing firepower! A massive display of new equipment and combat modes, drones become battlefield weapons, defeating the enemy silently!] (军事纪实 [Junmi Tianxia], October 29, 2024), YouTube video, . Return to text.

- Xiao Tianliang, Science of Military Strategy, 426–27. Return to text.

- Xiao Tianliang, Science of Military Strategy. Return to text.

- Zhang Pan 张攀, “信息技术环境下武警部队装备数字化建设探析” [An analysis of the digitalization of equipment in the People’s Armed Police in the context of information technology], 科技与创新 [Science and Technology & Innovation] 13 (2024): 162–68. Return to text.

- Zhao Lei, “Armed Police Must Obey Party,” China Daily, January 11, 2018, www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201801/11/WS5a568f1ca3102e5b17374094.html. Return to text.

- “习主席在解放军和武警部队代表团全体会议上的重要讲话在全军引起热烈反响” [Xi Jinping’s important speech at the full meeting of the PLA and PAP delegations has sparked a warm response across the entire military], 解放军报 [PLA Daily], March 9, 2023, http://www.mod.gov.cn/gfbw/qwfb/16373778.html. Return to text.

- Xiao Tianliang, Science of Military Strategy, 423. Return to text.

- He Xiaobiao 何晓标, “武警部队参与处置群体性事件研究——以广东武警为例” [A study on the People’s Armed Police’s participation in handling mass incidents: A case study of the Guangdong Armed Police], 万方数据 [Wanfang Data], May 31, 2011, https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/thesis/Y9004082. Return to text.

- Wuthnow, China’s Other Army, 7. Return to text.

- Peter Mattis, “In a Fortnight: Wukan Uprising Highlights Dilemmas of Preserving Stability,” China Brief 11, no. 23 (December 2011): 1–3. Return to text.

- Tania Branigan and Randeep Ramesh, “Gunfire on the Streets of Lhasa as Rallies Turn Violent,” The Guardian, March 14, 2008, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/mar/15/tibet.china1. Return to text.

- “Biru Villagers Respond with Protests to Chinese Flags, Security, Detentions,” Congressional-Executive Commission on China, November 20, 2013, https://www.cecc.gov/publications/commission-analysis/biru-villagers-respond-with-protests-to-chinese-flags-security. Return to text.

- Wuthnow, China’s Other Army, 12–13. Return to text.

- Xiao Tianliang, Science of Military Strategy, 424. Return to text.

- Zhang Yuliang 张玉良, ed., 战役学 [Science of campaigns], 2nd ed. (国防大学出版社 [PLA National Defense University Press], 2006), 123. Return to text.

- “与香港仅一湾之隔 中国数千武警集结深圳湾体育中心” [With only a bay between Hong Kong and China, thousands of armed police gather at Shenzhen Bay Sports Center], 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], August 16, 2019, https://www.zaobao.com.sg/special/report/politic/hkpol/story20190816-981254. Return to text.

- Greg Torode, “Exclusive: China’s Internal Security Force on Frontlines of Hong Kong Protests,” Reuters, March 18, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/world/exclusive-chinas-internal-security-force-on-frontlines-of-hong-kong-protests-idUSKBN2150JQ. Return to text.

- “习主席视察武警第二机动总队时的重要讲话在全军引起热烈反响” [Xi Jinping’s important speech during his inspection of the PLA’s Second Mobile Division has sparked a warm response across the entire military], 解放军报 [PLA Daily], March 28, 2021, http://www.mod.gov.cn/gfbw/sy/tt_214026/4882167.html. Return to text.

- Zhang Yuliang, Science of Campaigns, 123. Return to text.

- Wang Shucheng 王树成 and Xie Feng 谢峰, “武警部队后方防卫作战指挥要做到‘三个坚持’ ” [The three principles for the command of rear defense operations of the People’s Armed Police], 国防 [National Defense] 4 (2012): 54–55. Return to text.

- Xiao Tianliang, Science of Military Strategy, 431. Return to text.

- “武警后勤学院概况” [Overview of the People’s Armed Police Logistics Academy], 解放军报 [PLA Daily], June 18, 2014, http://www.81.cn/rdzt/2014/0421bkjx/2014-06/18/content_5964263.htm. Return to text.

- Sun Xingwei 孙兴维 and Gao Liying 高立英, “解放军全力支援地方打好疫情防控攻坚战” [People’s Liberation Army fully supports local governments in fighting the battle against the epidemic], China Military Online, Jan. 26, 2020, http://www.81.cn/zt/2020nzt/dyyqfkzjz/jdcy/9726397.html. Return to text.

- Zhang Fu 张辅 and Li Chaoqiang 李超强, “武警特警学院抓好初级指挥教育培训 提高学员综合能力” [The PAP Special Police Academy strengthens basic command training to enhance cadets’ comprehensive abilities], 解放军报 [PLA Daily], December 13, 2022, http://www.mod.gov.cn/gfbw/wzll/4928261.html. Return to text.

- Anti-Terrorism Law of the People’s Republic of China (promulgated by the Stand. Comm. Nat’l People’s Cong., Dec. 27, 2015) (China); and “中国两支最强反恐部队将首次共同赴俄参加演习” [China’s two strongest counterterrorism units to jointly participate in a Russian exercise for the first time], 新浪军事 [Sina Military], June 28, 2016, https://mil.sina.cn/zgjq/2016-06-28/detail-ifxtmwei9438201.d.html. Return to text.

- Jiang Yang 姜杨, “武警江苏总队组织开展军地联合投送训练” [The Jiangsu PAP Contingent organizes military-civilian joint deployment training], 荔枝网 [Litchi News], July 19, 2023, https://news.jstv.com/a/20230719/0d25b6325e184b528fcb72bb845ff226.shtml. Return to text.

- “滴水湖上“激战正酣”,武警上海总队开展为期十天冲锋舟集训” [Fierce battle on Dishui Lake: Shanghai PAP conducts ten-day assault boat training], 澎湃新闻 [The Paper], August 27, 2020, https://m.thepaper.cn/wifiKey_detail.jsp?contid=8904336. Return to text.

- “安徽某部实战化练兵 锻造特战‘武教头’ ” [Anhui unit conducts real-combat training to forge special operations “instructors”], 人民网-安徽频道 [People’s Daily Online – Anhui Channel], June 24, 2020, http://ah.people.com.cn/GB/n2/2020/0624/c358428-34111592.html; and Gao Yujiao 高玉娇 et al., “精武强能担使命——记武警第二机动总队某支队五中队” [Strengthening combat skills to fulfill the mission: A report on the fifth company of a unit in the Second Mobile Contingent of the People’s Armed Police], 新华社 [Xinhua], September 21, 2023, http://www.news.cn/politics/2023-09/21/c_1129875965.htm. Return to text.

- Reid Standish, “From a Secret Base in Tajikistan, China’s War on Terror Adjusts to a New Reality,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, October 14, 2021, https://www.rferl.org/a/tajikistan-china-war-on-terror-afghan/31509466.html. Return to text.

- Stephen Blank, “China’s Military Base in Tajikistan: What Does It Mean?,” The Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst, April 18, 2019, https://www.cacianalyst.org/publications/analytical-articles/item/13569-chinas-military-base-in-tajikistan-what-does-it-mean?.html. Return to text.

- “习近平视察武警第二机动总队” [Xi Jinping inspects the 2nd Mobile Contingent of the People’s Armed Police], 新华社 [Xinhua], March 26, 2021, https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-03/26/content_5596019.htm. Return to text.

- Kevin McCauley, “Amphibious Operations: Lessons of Past Campaigns for Today’s PLA,” RealClearDefense, February 27, 2018, https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2018/02/27/amphibious_operations_lessons_of_past_campaigns_for_todays_pla_113123.html. Return to text.

- He Xiaobiao, “Study.” Return to text.

- Zhang Pan, “Analysis.” Return to text.

Disclaimer: The articles and commentaries published on the CLSC website are unofficial expressions of opinion. The views and opinions expressed on the website are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Department of Defense, the Department of the Army, the US Army War College, or any other agency of the US government. Authors of Strategic Studies Institute and US Army War College Press products enjoy full academic freedom, provided they do not disclose classified information, jeopardize operations security, or misrepresent official US policy. Such academic freedom empowers them to offer new and sometimes controversial perspectives in the interest of furthering debate on key issues. The appearance of external hyperlinks does not constitute endorsement by the Department of Defense of the linked websites or the information, products, or services contained therein. The Department of Defense does not exercise any editorial, security, or other control over the information you may find at these locations.