— 6 —

Zeitenwende Energy Policy

Loyle Campbell and Tim Bosch

©2025 Tim Bosch

Download Full PDF

Introduction: Germany’s Evolving Energy Security

Russian fossil fuels underpinned decades of German economic success by providing a competitive edge for industry and a seemingly reliable energy supplier in Russia. The latter became a working assumption that was supported by political and business stakeholders. Energy relations with Russia underwrote German strategic decision making, even after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014. These energy relations changed in February 2022 when Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Such irrefutable hostility forced Berlin to place energy at the heart of the Zeitenwende.

The invasion had broad implications for European security. Because energy revenues constitute a significant income stream for the Russian state, Europe’s import dependencies were facilitating a threat to its security. As European countries provided military equipment to Ukraine and agreed on ever-tighter economic sanctions, energy policy also needed readjustment, lest it undermine the strategic objective to confront Russian aggression.

Germany was particularly vulnerable because Russia was its primary natural gas supplier.1 In the weeks following Russia’s invasion, Germany switched to neighboring and overseas suppliers. Energy-saving efforts at the industry and household levels, a temporary increase in coal usage, and a brief extension of nuclear power helped fill supply gaps. Natural gas imports from Russia quickly dropped over the summer of 2022. Vice Chancellor Robert Habeck called this decrease a “combined national effort.”2

But the turnaround brought new issues, such as volatile energy prices and geopolitical uncertainty. This chapter conducts a retrospective assessment of the Zeitenwende’s energy policy dynamics to identify the successes, constraints, and remaining challenges. Our assessment is guided by the World Energy Council’s energy trilemma framework, which assumes policymakers simultaneously aim to achieve security of supply, energy equity (affordability), and environmental sustainability.3 This framework allows us to assess how these priorities are balanced by governments pursuing a resilient energy system amidst geopolitical disruption and competing needs.4 The framework is relevant to assessing the Zeitenwende, as the German government historically prioritized sustainability and affordability but neglected energy security, which contributed to Germany’s vulnerability.5

Prewar Context of German Energy Policy

Despite criticism, German energy policy has had successes. Going into 2022, interconnectors offered Germany diverse electricity imports—such as Danish wind, French nuclear, and Swiss and Swedish hydropower. Pipelines also connected gas producers and hubs such as Norway and the Netherlands. Germany also exploited domestic lignite and, at the time, had the world’s third-largest installed capacities for solar and wind at 58.4 gigawatts (GWs) and 63.7 GWs, respectively.6 The latter was the result of the Energiewende or energy transition—a policy advocating energy efficiency, renewable deployment, and a nuclear phaseout.7

In this context, the core issues were the magnitude of Russian energy imports and how they came to underwrite national energy policy to a point where other options were deprioritized. Existing nuclear plants were phased out ahead of schedule.8 At the same time, domestic conventional gas production was allowed to decline.9 Nonconventional gas production also faced legal barriers—despite the presence of significant reserves.10

Renewables also received inconsistent attention. Easy-to-reach deployment targets were prioritized while politically challenging grid and transmission expansion faced legal-administrative hurdles. Cheap gas also deferred investment in electric alternatives for residential and industrial uses.11

Reacting to External Shock: Primacy of Security of Supply

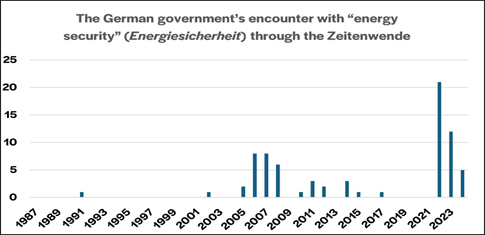

Over the past few decades, German politics rarely put energy security on the agenda. The occasions where energy security was on the agenda were in response to external shocks. As figure 6-1 shows, the term energy security (Energiesicherheit) was mentioned in 37 of the 15,609 documented public speeches from 1987 to 2021—most of which were during the 2006–2009 Ukraine-Russia gas disputes.12 This number pales in comparison to 38 mentions in 1,137 speeches in the first two and a half years following Russia’s full-fledged invasion of Ukraine.

Figure 6-1. References to energy security (Energiesicherheit) in German officials’ speeches

The energy crisis pulled attention to a traditional notion of energy security in terms of security of supply. This was the case for natural gas, where efforts to diversify and manage supply were decisive. Liquid natural gas (LNG) import terminals were announced three days after the invasion of Ukraine.13 Within 10 months, Germany had its first licensed and operating floating storage regasification unit (FSRU). Legislation such as the Gas Storage Act and the Emergency Plan for Gas helped the government manage the gas network and build a strategic stockpile, while others accelerated new projects.14 At the same time, ministers visited the United States and Qatar to secure long-term offtake agreements with new suppliers.15 Germany also imported more gas from neighbors via pipeline, and implemented a range of energy-saving measures to curb gas demand.16 Significant energy savings at the household and industry levels also contributed to managing the 2022 energy crisis.17

These saving measures also reinforced the power sector and ran in conjunction with a brief extension of nuclear and coal power generation. The operations of two of the three remaining nuclear plants, planned for a 2022 phaseout, were extended until April 2023.18 The extensions, particularly for coal, were accompanied by a new strategic coal reserve.19 Temporarily expanding coal power was done reluctantly, as the government recognized the trade-offs between energy security and sustainability. The expanded use of coal (alongside oil) implied a rise in emissions from the energy sector in 2022, with Germany missing its mitigation targets that year.20 But in 2023, coal power–related emissions dropped to the lowest level since the 1960s, and coal-fired power plants continue to retire early.21 In the medium term, a legal pathway foresees the exit from coal-fired power occurring in the 2030s. Although a remaining baseload capacity will ensure energy security, coal plays an ever-smaller role in Germany’s energy system.

The situation for coal contrasts with the situation for natural gas. Given the phasedown of both domestic nuclear and domestic coal, natural gas had long been identified as a transition technology. Its geopolitical significance increased with reinforced imports of pipeline gas from neighboring countries and new LNG supplies via sea routes. In 2022–23, Germany launched three FSRUs, which in 2023 covered about 7 percent of total imports.22 Although this percentage is currently a moderate amount, the FSRUs are to be replaced by higher-capacity, permanent onshore facilities starting in 2027.23 With shifting import patterns, energy trade is now also increasingly in the mutual economic interest of Germany and its suppliers. Since 2023, natural gas trade between the United States and the EU has increased: Europe has become the main destination for US LNG and is willing to pay a premium for secure gas, and several EU countries (including Germany) rely on the United States to fill supply gaps. Furthermore, at least a share of Germany’s supply has been friendshored to partners such as Norway.24

German oil supplies were also hit, especially in early 2022. In 2021, Russia was Germany’s largest supplier, accounting for more than a third of German imports. But in June 2022, the EU imposed sanctions restricting the purchase or import of Russian crude oil and other petroleum products. Germany brought down Russian oil imports and diversified its supply from third countries, including Norway, the United Kingdom, and Kazakhstan as top suppliers.25 The United States also steeply increased oil exports to Europe, with Germany as one destination.26

High Economic Costs of Managing the Energy Crisis

As gas and electricity prices spiked in 2022–23, the government passed relief packages with tax breaks for lower- and middle-income citizens, direct income-support measures, instruments to reduce energy-transport costs, and temporary price caps for electricity and gas for businesses and households. The long-term total cost of measures to curb prices and counter inflation was estimated at up to €300 billion.27 Relief measures mitigated but could not prevent rising costs for consumers. In line with the EU trend, spiking energy prices are estimated to have led to net welfare losses across income groups, with an estimated average loss of 2.9 percent in 2022.28

Regarding industry, targeted relief measures, coupled with demand-side reductions, helped adapt to rising costs. Thus, “the curtailment and suspension of Russian gas deliveries did not create any physical supply interruption,” and most companies managed to mitigate wholesale price increases.29 Although fears of broad deindustrialization have been avoided, some energy-intensive industry left Germany, especially companies relying heavily on gas as a direct energy source or feedstock.30 Industrial power and gas prices have come down from their 2022 peak but will remain well above precrisis levels. These prices, along with other structural factors, are driving the discussion around the need for green industrial policy.

Long-term higher natural gas prices also affect the power sector. Natural gas used in periods of peak demand still sets electricity prices because European power markets follow merit-order pricing.31 The merit order is a market structure that links electricity prices to the price set by the highest-cost marginal producer. In other words, the most expensive plant feeding power into the system sets the price, which can be a problem when inefficient gas power plants run for long periods of time. For instance, in 2022, natural gas set power prices 63 percent of the time, although it only makes up 20 percent of Europe’s electricity mix—a trend that applies to Germany.32 Reducing the power price in the long run is complex and requires reforms targeting EU energy markets. But one factor in price reductions lies in the buildup of a diverse mix of renewables, which would help displace gas capacity from peak pricing.

The Growing Link Between Energiewende and Energy Security

The expedited LNG infrastructure, nuclear and coal extensions, and energy-saving efforts filled Germany’s immediate energy gaps. But these were crisis management measures and should not be conflated with the defining spirit of the Zeitenwende, which aims to shift away structurally from fossil fuel import dependency and improve the resilience of Germany’s energy system. These aims are clearer when assessing the role of renewables in Germany’s future energy system, with politicians even calling renewables “freedom energies.”33 Such a framing highlights how renewables are increasingly seen as the primary vehicle for Germany to realize greater energy independence and resilience.

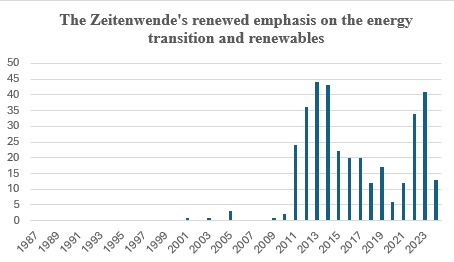

Figure 6-2. References to energy transition (Energiewende) in speeches of German officials

The growing link between the energy transition (Energiewende) and energy security is visible in political statements, as the term has seen a resurgence (see figure 6-2).34 The legislative packages launched in 2022 illustrate this alignment.35 The so-called Easter package outlined sweeping revisions to the legislation underpinning renewable energy, with many changes focusing on bottlenecks that constrained further expansion and integration of renewables.36

The first key legal reform designated renewable projects as an overriding public interest.37 This adjustment aims to accelerate permit processing while also mitigating the grounds to block or delay projects. The second reform was the amendment to the Renewable Energy Sources Act that raised targets to have 80 percent renewable electricity by 2030, with specific targets for wind and solar capacity.38 Such reforms are critical, as they contribute to achieving emissions mitigation and reaching net-zero emissions by 2045, as stipulated by Germany’s Climate Change Act. Ambitious emissions mitigation is required under the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany (Germany’s constitution), as ruled by the Federal Constitutional Court, which is notable in this context.39

Other revisions targeted rules on spatial planning, permitting, and siting for onshore wind. Onshore wind was a priority because, in 2022, Germany had nearly 800 percent more wind capacity stuck in permitting than under construction, with average processing times from five to eight years. Arduous rules on turbine spacing, paired with restrictive species protections, reduced deployment zones.40 Adjustments to resolve this issue include rules obliging states to ensure at least 2 percent of Germany’s surface area is made available for onshore wind by 2032 and revisions to the Federal Nature Conservation Act attempting to rebalance environmental protection around renewable infrastructure.41

Further changes targeted grids, offshore wind, and energy efficiency. Grid legislation was amended to simplify the planning and expansion process to meet the technical needs of renewables more effectively.42 Offshore wind targets were raised, the bidding model for public tenders was amended, and a pipeline of new tenders was launched.43 The Energy Efficiency Act was altered to raise standards for the building and heating sectors to reduce energy consumption.44

These changes culminate in some initial positive trends. Renewables as a share of total power generation climbed from 45.6 percent in 2022 to 59 percent as of September 2024.45 In 2023 alone, the solar capacity deployment rate doubled from 2022, while wind generated more electricity than coal for the first time.46 This trend will continue, as the 4.3 GW of annually permitted wind capacity in 2022 rose to 7.4 GW in 2023 and 4.7 GW in the first half of 2024.47 Public tenders for offshore wind could complement this trend with 30 GW of capacity by 2030.48 If these trends continue, International Energy Agency projections see Germany realizing 100 GW of onshore wind, 30 GW of offshore wind, and 200 GW of solar photovoltaic by 2030.49

These changes have strategic implications for energy security, as Germany is working to redress structural issues to improve the effectiveness of its power system. Germany’s nontrivial legal, regulatory, and administrative revisions strengthen the security and reliability of the supply by ensuring projects move forward on time and domestic resources are optimized. This effort requires broad deployment, as wind blowing today cannot be harnessed tomorrow. Germany’s renewable energy resources are strategic assets: Emissions mitigation through the buildup of renewables supports sustainability targets and constitutes an investment in national security.50

Remaining Challenges

Through the Zeitenwende, policymakers needed to make consequential decisions under exceptional circumstances: They faced geopolitical turmoil, were forced to move on short time horizons, and often based decisions on imperfect information. Against this backdrop, the avoidance of the worst impacts of the energy crisis constitutes a remarkable achievement. But several structural challenges remain that will require the future government’s attention to improve resilience.

First, the renewed orientation toward renewable energies brings new challenges for German energy security. Renewables are still nondispatchable and although broader deployments across different technologies (for example, batteries) mitigate this issue, it remains a challenge—particularly for periods where peak demand meets weak generation (for example, on a nonwindy evening). Renewables also highly depend on backup capacity and network expansion. If either are disrupted, then the vulnerability could worsen. New technologies also create new dependencies from dominant producers, such as China, and hence come with their own issues.

During the transition, Germany’s shift to renewables and energy efficiency poses a challenge to affordability. New renewable projects and efficiency improvements have different cost structures than amortized fossil systems. Even if the projects cost less over time, the capital required for installation is high. For example, the KfW Bankengruppe estimates the German grid alone will need some €300 billion of investments by 2050.51 The debt brake in Germany’s constitution currently imposes strict limits on public spending, and the traffic-light coalition, which broke apart in November 2024, could not find consensus on reform. As fiscal space is restricted and Germany’s economy stagnates, debates about the reform of the debt brake will be a decisive agenda item for the new government.

Second, the move toward LNG supplies has strategic implications: Germany aims to replace FSRUs with permanent landside regasification units as of 2026–27, with permits running until 2043.52 Although LNG currently accounts for a small share of imports, the planned infrastructure would raise import capacities. At the time of writing, the investment decisions for two of the three planned landside facilities have been made, cementing LNG’s prominent role in Germany’s energy mix.

Some analysts fear expanding infrastructure may exceed domestic demand and create stranded assets.53 The embrace of LNG has also raised concerns about sustainability: Studies project if all planned LNG terminals were operating at capacity, they may compromise climate mitigation goals.54 The situation is complicated by a controversy about the green readiness of LNG infrastructure.55 But whether this infrastructure could comply with green criteria is disputed.56

On the other hand, a share of this capacity is intended to supply landlocked neighbors, such as Czechia or Austria.57 One reading of Germany’s changing natural gas politics is it shifts from a formerly unilateral import strategy toward a more Europeanized and connected approach. Moreover, policymakers plan with a significant security buffer, where flexible capacities can absorb supply shocks. The LNG infrastructure rarely runs at full capacity and is planned based on redundancy. If one large supplier (for example, Norway) was disrupted, it could be compensated by more LNG. From this standpoint, Germany’s LNG capacities come with a significant security premium factored into them. In any case, Germany will continue to be subject to the volatility of gas markets (for example, through geopolitical shocks or long-term shifts in demand).

Third, the turn away from Russian energy supplies, although constituting a significant strategic shift, requires perseverance and continued engagement. Entanglement with Russian energy assets continues to cast a long shadow. Russian energy company Rosneft has long held a stake in several German refineries fitted to run on Russian crude. Replacing this stake has been a challenge, as only a few suppliers—notably including Kazakhstan—can offer a direct substitution. But Kazakhstan is landlocked and oil deliveries flow through Russian pipelines.58 These factors have prevented Berlin from outright seizing one of Rosneft Germany’s largest assets for fear of having supplies disrupted.59 The government expects Rosneft to sell its assets, but the outcome remains unclear. This case illustrates the pervasive nature of Russian energy infrastructure and the complexities of decoupling.

An ongoing discussion about the future of natural gas imports at the EU level poses similar challenges: The European Commission is currently in negotiations with Azerbaijan to replace Russian supplies via pipeline. But some have concerns this agreement may indirectly benefit Russia, because Russia would in turn increase its exports to Azerbaijan (thus leading to additional Russian revenues), and because Azerbaijan gas may flow through pipelines owned by Russian company Gazprom.60 So far, Germany has advocated for decoupling, but several Central European countries continue to rely on Russian supplies. European disunity may undermine resilience against hybrid threats and complicate the strategic countering of Russian aggression. Against this backdrop, to Europeanize discussions about energy security and future import policies will be important.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Building on a broader consideration of security, affordability, and sustainability, the Zeitenwende in energy policy may be characterized as a qualified success. In particular, the Scholz government ensured the continued flow of energy while mitigating rising costs for households and industry through determined support packages. Of course, the billions of euros spent on managing the external shock could have been used earlier, had the construction of a more resilient energy system based on renewables and diverse imports been construed as a national security priority.

But this lacuna is not the responsibility of the outgoing government led by Chancellor Olaf Scholz. The lacuna is the outcome of a long-standing overreliance on fossil fuels from an authoritarian (and now forcefully aggressive) former supplier. Against this backdrop, the past several years can be seen as a salutary shock: Renewable energies have rightly been identified as the central opportunity and form the basis of German energy security, while flexible natural gas infrastructures fill supply gaps and de-risk imports.

But uncertainties persist around the role of natural gas, which may create new path dependencies. The deeper and quicker adoption of green technologies compounds this risk by shifting dependencies to producers of green technologies, where Chinese actors play an outsized role. Policymakers are aware of this issue, and the general securitization of energy policy puts de-risking and dependency reduction as key priorities. To create balance, the next German and American governments should do the following.

-

Commit to an irreversible transition where Germany is independent from Russian fossil fuels. German dependence on Russian energy has been cut while LNG import capacity and renewables have been scaled. The outgoing German government has set the stage to deliver a permanent shift away from Russian energy. But delivering on this shift remains a political choice, as some in Berlin may one day look to rebuild energy relations with Russia. This risk remains, especially if the Russia-Ukraine War comes to an end. Even if this occurs, the new German government should continue to commit to German independence. To support this effort, leaders in the United States should continue to offer Germany and Europe stable energy relations.

-

Replicate the decisive strategy to diversify natural gas into green supply chains. Supply chains for green technologies are concentrated around China. Although decoupling is not realistic, diversifying supply chains and building alternative capacity is in the American and German national interest. But this is a complex process with long investment cycles and requires many partners. The new German government should support a common European approach. The EU’s emerging green industrial policy bears opportunities, including the further development of measures such as Important Projects of Common European Interest and the EU Innovation Fund.61 Transatlantic cooperation through means such as the Minerals Security Partnership could complement these opportunities to engage new suppliers.

-

Continue realizing the strategic evolution of energy security by taking steps to Europeanize energy policy. Deeper collaboration with neighbors and the EU more broadly will help prevent a reversion to the previous unilateral approach. The joint offshore wind targets for the North and Baltic Seas go in the right direction.62 Combined, these targets represent hundreds of GWs in capacity and could strengthen energy security for a dozen member states. Pairing these targets with a broader and more proactive engagement will further build German credibility on energy policy.

-

Establish EU-US dialogue to align LNG imports with sustainability criteria. The EU’s Methane Regulation, which became effective on August 4, 2024, foresees monitoring, reporting, and verification measures for the LNG supply chain. As of 2027, EU LNG importers will need to show supply contracts fulfill the same standards as the EU’s monitoring, reporting, and verification measures, which includes emissions intensity.63 As of August 2028, importers will have to report on the methane intensity of LNG imports concluded or renewed after August 4, 2024.64 These changes raise questions about the feasibility of future imports of US LNG, which is relatively emissions intensive. To ensure compliance and avoid potential supply disruptions, the United States and the EU should engage in foresighted dialogue about emissions mitigation options or a regulatory equivalence to the Methane Regulation in the United States. The latter could exempt the importer from reporting duties.65

-

Refocus efforts to use the EU-US Trade and Technology Council to resolve emerging divergences on green industrial policy and efforts to de-risk from China. The American and European green industrial policies and relationships with Chinese technology are going at different speeds and, in some cases, different directions, as evidenced by the divergence between tariffs applied to Chinese electric vehicles. The EU-US Trade and Technology Council was launched to focus transatlantic efforts on key trade, economic, and technology issues, but has not been used to its full potential. The EU and the United States should engage in deeper sector-specific discussions about adopting common standards for diversifying and de-risking green supply chains.

Endnotes

- In 2021, Russian imports accounted for as much as 52 percent of German natural gas supplies. “Bundesnetzagentur Publishes Gas Supply Figures for 2022,” Bundesnetzagentur, January 6, 2023, https:// www.bundesnetzagentur.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/EN/2023/20230105 _RueckblickGas2022.html#:~:text=The%20total%20volume%20of%20natural,the%20course%20of%20the%20year. Return to text.

- “Habeck: ‘We Need a Combined National Effort,’ ” Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, August 13, 2022, https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2022/08/20220813-we-need-a-combined-national-effort.html. Return to text.

- Energy security “reflects a nation’s capacity to meet current and future energy demand reliably, withstand and bounce back swiftly from system shocks with minimal disruption to supplies.” Energy equity “assesses a country’s ability to provide universal access to affordable, fairly priced and abundant energy for domestic and commercial use.” Environmental sustainability “represents the transition of a country’s energy system toward mitigating and avoiding potential environmental harm and climate change impacts.” See “World Energy Trilemma Framework,” World Energy Council, n.d., accessed on October 20, 2024, https://www.worldenergy.org/transition-toolkit/world-energy-trilemma-framework. Return to text.

- Most notably, the World Energy Council annually publishes the World Energy Trilemma Report, which focuses on various world regions. See “World Energy Trilemma Report 2024,” World Energy Council, n.d., accessed on October 20, 2024, https://www.worldenergy.org/publications/entry/world-energy-trilemma-report-2024. Return to text.

- Constanze Stelzenmüller, “Energy Trilemma Causes a Headache for Germany’s New Leaders,” Brookings Institution, January 18, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/energy-trilemma-causes-a-headache-for-germanys-new-leaders/. Return to text.

- Arvydas Lebedys et al., Renewable Capacity Statistics 2022 (International Renewable Energy Agency, 2022), 14, 21. Return to text.

- Simon Evans, “The History of the Energiewende,” Carbon Brief, September 21, 2016, https://www .carbonbrief.org/timeline-past-present-future-germany-energiewende/. Return to text.

- In March 2011, Chancellor Angela Merkel announced Germany would accelerate plans to phase down domestic nuclear energy capacity, which included immediately suspending several operational plants. This announcement was in direct response to the Fukushima accident. The extent of how this action impacted the European and German energy system, or its security, remains contested. Nevertheless, the stable supply of Russian gas facilitated this decision and various price projections for household and industry electricity were highly sensitive to gas pricing because of the gas generation’s strong role in setting the price through its positioning in the merit order. See Brigitte Knopf et al., “Germany’s Nuclear Phase-out: Sensitivities and Impacts on Electricity Prices and CO2 Emissions,” Economics of Energy & Environmental Policy 3, no. 1 (March 2014): 14–15. Return to text.

- German domestic gas output fell by 80 percent from 2000 –24. See “Germany: Natural Gas Supply,” International Energy Agency (IEA), n.d., accessed on August 15, 2024, https://www.iea.org/countries/germany/natural-gas. Return to text.

- For example, fracking of shale formations has been il legal in Germany since 2017. The Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe estimates German shale reserves range between 380 to 2,340 billion cubic meters of gas, which is equivalent to roughly five to 20 years of domestic consumption. See Julian Wettengel, “Q& A – Energy Crisis Reignites Debate About Fracking in Germany,” Clean Energy Wire, January 2, 2023, https://www.cleanenergywire.org/factsheets/qa-energy-crisis-reignites-debate-about-fracking-germany; and Stefan Ladage et al., Schieferöl und Schiefergas in Deutschland: Potenziale und Umweltaspekte (Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe, January 2016), 9. Return to text.

- In 2022, natural gas accounted for 39 percent and 34 percent of residential and industrial total energy consumption, respectively, whereas electricity represented 21 percent and 33 percent respectively. “Germany: Efficiency & Demand,” IEA, n.d., accessed on August 20, 2024, https://www.iea.org/countries/germany/efficiency-demand. Return to text.

- Figure 6-1 is based on a key-term search of the collection of authorized speeches of the president of the federal republic, the chancellor, and members of the federal government. The year 2024 is incomplete, with a cutoff date of August 16, leading to relatively fewer speeches for 2024 and fewer mentions of energy security. Figure 6-1 is the author’s own illustration, building on a search on the federal government’s bulletin of authorized speeches at: “Bulletin,” Die Bundesregierung, n.d., accessed on December 19, 2024, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/service/newsletter-und-abos/bulletin. Return to text.

- Naida Hakirevic Prevljak, “Germany to Break Free from Russian Gas with Two LNG Terminals,” Offshore Energy, February 28, 2022, https://www.offshore-energy.biz/germany-to-break-free-from-russian-gas-with-two-lng-terminals/. Return to text.

- The Gas Storage Act entered force on April 30, 2022, and it obliges all gas operators in Germany to keep their storage facilities full. “Gas Storage Act Enters into Force Tomorrow - Important Contribution to Security of Supply,” Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Clim, April 29, 2022, https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2022/04/20220429-gas-storage-act-enters-into-force-tomorrow.html; Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, FAQs – Emergency Plan for Gas (Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, March 30, 2022); and “Federal Cabinet Adopts Tool to Help Formulate LNG Acceleration Act,” Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (website), May 10, 2022, https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Pressemitteilung en/2022/05/20220510-federal-cabinet-adopts-tool-to-help-formulate-lng-acceleration-act.html. Return to text.

- Gerald Traufetter, “German Economy Minister Celebrated in Washington,” Der Spiegel, March 2, 2022, https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/german-foreign-policy-reversal-german-economy-minister-celebrated-in-washington-a-305e363a-ef 8f-4947-9c55-fa1650191225; “Minister Habeck Visits Qatar and the UAE – Focus on Energy Security Matters,” Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (website), March 18, 2022, https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2022/03/20220318-minister-habeck-visits-qatar-and-the-uae-focus-on-energy-security-matters.html; and “ConocoPhillips and QatarEnergy Agree to Provide Reliable LNG Supply to Germany,” ConocoPhillips, November 29, 2022, https://www.conocophillips.com/news-media/story/conocophillips-and-qatarenergy-agree-to-provide-reliable-lng-supply-to-germany/. Return to text.

- Malte Humpert, “Norway Now Germany’s Largest Gas Supplier, Future Supply from Arctic to Support Exports,” High North News, January 11, 2023, https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/norway-now-germanys-largest-gas-supplier-future-supply-arctic-support-exports; and Rina Goldenberg, “Germany Implements Energy-Saving Rules,” Deutsche Welle, September 1, 2022, https://www.dw.com/en/germanys-energy-saving-rules-come-into-force/a-62996041. Return to text.

- Oliver Ruhnau et al., “Natural Gas Savings in Germany During the 2022 Energy Crisis,” Nature Energy 8 (2023): 621–28. Return to text.

- The two remaining nuclear plants, planned for a 2022 phaseout, were extended to operate until April 2023. The extension given to several dozen lignite plants was longer, considering some plants had their operation extended until early 2024. “Germany Plans to Keep 2 Nuclear Power Plants in Operation,” Deutsche Welle, September 27, 2022, https://www.dw.com/en/germany-plans-to-keep-2-nuclear-power-plants-in-operation/a-63258734; and “Cabinet Boosts Crisis-Preparedness for the Coming Winter: Lignite-Fired Power Plants to Come Back to the Market as Planned on 1 October 2022 – Grid Reserve to Be Extended Until 31 March 2024,” Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, September 28, 2022, https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2022/09/20220928-cabinet-boosts-crisis-preparedness-for-the-coming-winter.html. Return to text.

- Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, Second Energy Security Progress Report (Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, May 1, 2022). Return to text.

- Agora Energiewende, Rückkehr der Kohle macht Energiespareffekte zunichte und gefährdet Klimaziele (Agora Energiewende, January 4, 2023). Return to text.

- Although the drop in coal power–related emissions was partly due to lower power demand and growing energy imports (mainly generated from renewables), the growing share of renewables in power generation (up by 5 percent) also contributed to lower emissions. Agora Energiewende, Deutschlands CO2-Ausstoß sinkt auf Rekordtief und legt zugleich Lücken in der Klimapolitik offen (Agora Energiewende, January 4, 2024); and “Coal Phase-Out – No Coal-Fired Operation Bans Necessary for 2027 for First Time,” Bundesnetzagentur, September 2, 2024, https://www.bundesnetzagentur.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/EN/2024/20240902_Kohle.html?nn=691794. Return to text.

- “Bundesnetzagentur Publishes Gas Supply Figures for 2023,” Bundesnetzagentur, January 4, 2024, https://www.bundesnetzagentur.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/EN/2024/20240104_Gasversorgung2023.html. Return to text.

- But this would be a peak, as the 20 billion cubic meters of f loating capacity is contracted to be phased out throughout the 2030s. Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, Bericht des Bundeswirtschafts – und Klimaschutzministeriums zu Planungen und Kapazitäten der schwimmenden und festen Flüssiggasterminals (Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, March 3, 2023). Return to text.

- “The United States Was the World’s Largest Liquefied Natural Gas Exporter in 2023,” US Energy Information Administration, April 1, 2024, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=61683. Return to text.

- Statistisches Bundesamt, “Crude Oil Imports from Russia Down to 3,500 Tonnes in January 2023,” press release no. 098, March 13, 2023, https://www.destatis.de/EN/Press/2023/03/PE23_098_51.html. Return to text.

- “U.S. Crude Oil Exports Reached a Record in 2023,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, March 18, 2024, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=61584. Return to text.

- “Gas- und Strompreisbremse,” Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz, March 1, 2023, https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Artikel/Energie/strom-gaspreis-bremse.html. Return to text.

- Aaron Best et al., Who Took the Burden of the Energy Crisis? (Ecologic Institute, June 30, 2023). Return to text.

- Andreas Seeliger, German Industrial Gas: Crisis Averted, for Now (The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, November 2023), 10. Return to text.

- For example, BASF Aktiengesellschaft, the world’s largest chemicals company, has announced plans to move production from Germany to outside Europe. See Seeliger, German Industrial Gas, 8. Return to text.

- “What Does Merit Order Mean?,” Next Kraftwerke, n.d., accessed on October 20, 2024, https://www.next-kraftwerke.com/knowledge/what-does-merit-order-mean. Return to text.

- European Commission, The Future of European Competitiveness: Part A – A Competitiveness Strategy for Europe (European Commission, September 2024), 44. Return to text.

- This term was used by the former finance minister. See Christian Lindner, “Accepting the Challenge: A Liberalism for Tomorrow” (lecture, German Federal Ministry of Finance, Princeton, NJ, April 14, 2023). Return to text.

- Figure 6-2 is based on a key-term search of the collection of authorized speeches of the president of the federal republic, the chancellor, and members of the federal government. The year 2024 is incomplete, with a cutoff date of August 16, leading to relatively fewer speeches for 2024 and hence fewer mentions of the term. Figure 6-2 is the author’s own illustration, building on a search on the federal government’s bulletin of authorized speeches at: “Bulletin,” Die Bundesregierung, n.d., accessed on December 19, 2024, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/service/newsletter-und-abos/bulletin. Return to text.

- Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, Overview of the Easter Package (Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, April 6, 2022). Return to text.

- The package outlined revisions to legislation including, amongst others, the Renewable Energy Sources Act, the Offshore Wind Energy Act, the Energy Industry Act, the Federal Requirements Plan Act, and the Grid Expansion Acceleration Act. Return to text.

- Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, Easter Package. Return to text.

- “Ausgewählte Tagesordnungspunkte der 1023. Sitzung am 08.07.2022,” Bundesrat, n.d., https://www.bundesrat.de/DE/plenum/bundesrat-kompakt/22/1023/51.html. Return to text.

- Dana Schirwon, “The German Federal Constitutional Court’s Revolutionary Climate Ruling,” German Council on Foreign Relations, April 20, 2022, https://dgap.org/en/research/publications/german-federal-constitutional-courts-revolutionary-climate-ruling. Return to text.

- Nick Ferris, “Data Insight: 11.4GW More EU Wind Capacity Stuck in Permitting Than a Year Ago,” Energy Monitor, April 26, 2023, https://www.energymonitor.ai/tech/renewables/data-insight-11-4gw-more-eu-wind-capacity-stuck-in-permitting-than-a-year-ago/?cf-view; and Jan Stede et al., Way Off: The Effect of Minimum Distance Regulation on the Deployment and Cost of Wind Power (Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, 2021). Return to text.

- Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, Entwurf einer Formulierungshilfe der Bundesregierung (Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, June 15, 2022), 1; and Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, nukleare Sicherheit und Verbraucherschutz, Beschleunigung des naturverträglichen Ausbaus der Windenergie an Land (Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, nukleare Sicherheit und Verbraucherschutz, April 4, 2022). Return to text.

- “Gesetz zur Änderung des Energiewirtschaftsrechts im Zusammenhang mit dem Klimaschutz-Sofortprogrammund zu Anpassungen im Recht der Endkundenbelieferung,” Bundesgesetzblatt, July 19, 2022, https://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/start.xav?startbk=Bundesanzei-%20 ger_BGBl&jumpTo=bgbl122s1214.pdf#bgbl%2F%2F*%5B%40attr_id%3D%27bgbl122s1214.pdf%27%5D1669890275447. Return to text.

- “Zweites Gesetz zur Änderung des Windenergie-auf-See-Gesetzes und anderer Vorschriften,” Bundesgesetzblatt, July 20, 2022, https://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/start.xav?startbk=Bundesanzei-%20ger_BGBl&jumpTo=bgbl122s1325.pdf#bgbl%2F%2F*%5B%40attr_id%3D%27bgbl122s1325.pdf%27%5D1728442915086. Return to text.

- “Energy Efficiency Act: The Public Sector Set to Become a Role Model,” German Federal Government, April 19, 2023, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/federal-government/the-energy-efficiency-act-2184958. Return to text.

- “Monthly Renewable Share of Total Net Electricity Generation and Load in Germany in 2024,” Energy-Charts, n.d., accessed on October 20, 2024, https://www.energy-charts.info/charts/renewable_share/chart.htm?l=en&c=DE&year=2024&legendItems=11&share=ren_share_total. Return to text.

- “Net Installed Electricity Generation Capacity in Germany in 2023,” Energy-Charts, n.d., accessed on October 20, 2024, https://www.energy-charts.info/charts/installed_power/chart.htm?l=en&c=DE&year=2023&legendItems=3x27v; and “Germany: Sources of Electricity Generation,” IEA, n.d., accessed on October 20, 2024, https://www.iea.org/countries/germany/electricity. Return to text.

- Deutsche Windguard, Status of Onshore Wind Energy Development in Germany: First Half of 2024 (Deutsche Windguard, July 18, 2024), 11. Return to text.

- Deutsche Windguard, Status of Offshore Wind Energy Development in Germany: First Half of 2024 (Deutsche Windguard, July 15, 2024). Return to text.

- “Energy System of Germany,” IEA, n.d., accessed October 2024, https://www.iea.org/countries/germany. Return to text.

- Tim Bosch et al., Emissions Mitigation as a National Security Investment, German Council on Foreign Relations Policy Brief No. 22 (German Council on Foreign Relations, July 2023). Return to text.

- “Germany Needs $325 Bln of Power Grid Investments by 2050, Kf W Says,” Reuters, July 9, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/germany-needs-325-bln-power-grid-investments-by-2050-kfw-says-2024-07-09/. Return to text.

- Lucy Hine, “Germany’s FSRUs to Be Sublet from 2027 as Land-Based Terminals Start Up,” Upstream, December 13, 2024, https://www.upstreamonline.com/lng/germany-s-fsrus-to-be-sublet-from-2027-as-land-based-terminals-start-up/2-1-1753640. Return to text.

- See Christian von Hirschhausen et al., Gasversorgung in Deutschland stabil: Ausbau von LNG-Infrastruktur nicht notwendig, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung aktuell No. 92 (Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, 2024). Return to text.

- This issue is in fact not confined to Germany but extends to broader concerns about the potential incompatibility of natural gas projects with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Niklas Höhne et al., German LNG Terminal Construction Plans Are Massively Oversized (New Climate Institute, December 2022); and Claire Stockwell et al., “Massive Gas Expansion Risks Overtaking Positive Climate Policies,” Climate Analytics, November 10, 2022, https://climateanalytics.org/press-releases/massive-gas-expansion-risks-overtaking-positive-climate-policies. Return to text.

- The German government emphasizes liquified natural gas terminals in Brunsbüttel and Wilhelmshaven will be equipped for the import of green hydrogen derivatives, in particular ammonia. See “The Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action Presents a Report on the Plans for Floating and Fixed LNG Terminals and Their Capacities,” Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, March 3, 2023, https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2023/03/20230303the-federal-ministry-for-economic-affairs-and-climate-action-presents-a-report-on-the-plans-for-floating-and-fixed-lng-terminals-and-their-capacities.html. Return to text.

- Stéphanie Nieuwbourg, “Why Backing Germany’s LNG Investment Is a Roadblock – Not a Bridge to the Future,” Euractiv, July 1, 2024, https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/opinion/why-backing-germanys-lng-investment-is-a-roadblock-not-a-bridge-to-the-future/. Return to text.

- Alexandra Gritz and Guntram Wolff, “Gas and Energy Security in Germany and Central and Eastern Europe,” Energy Policy 184 (January 2024). Return to text.

- Victor Jack, “Germany Tallies Risks as It Weighs Rosneft Refinery Seizure,” Politico, February 15, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/germany-rosneft-refinery-russia-ukraine-war/. Return to text.

- At the time of this writing, the German government has again extended the trusteeship over Rosneft Germany. See Riham Alkousaa and Christoph Steitz, “Germany Extends Trusteeship over Rosneft Assets, Economy Ministry,” Reuters, September 9, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/germany-extend-rosneft-trusteeship-source-2024-09-02/. Return to text.

- Gabriel Gavin, “Europe’s Azerbaijan Gas Gambit Is Good News for Russia,” Politico, November 20, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-azerbaijan-gas-gambit-good-news-russia/; and Gabriel Gavin et al., “EU Wants Azerbaijan to Fuel Russian Gas Pipeline in Ukraine,” Politico, June 13, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-asks-azerbaijan-replace-russian-gas-transit-deal-ukraine-expiring/. Return to text.

- For an overview of the current instruments of EU green industrial policy, see Simone Tagliapietra et al., “Europe’s Green Industrial Policy,” Información Comercial Espanola 932 (2023): 51– 62. Return to text.

- Kira Taylor, “North Sea Countries Aim for 300 GW of Offshore Wind Energy by 2050,” Euractiv, April 25, 2023, https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/north-sea-countries-aim-for-300-gw-of-offshore-wind-energy-by-2050/; and “Baltic Sea Countries Sign Declaration for More Cooperation in Offshore Wind,” Wind Europe, August 30, 2022, https://windeurope.org/newsroom/press-releases/baltic-sea-countries-sign-declaration-for-more-cooperation-in-offshore-wind/. Return to text.

- “The EU Methane Reduction Regulation Is Now in Force, What Is the Impact on LNG Imports to the EU?,” Norton Rose Fulbright, August 2024, https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/de-de/wissen/publications/e25fed92/the-eu-methane-reduction-regulation-is-now-in-force-what-is-the-impact-on-lng-imports-to-the-eu. Return to text.

- “EU Methane Reduction Regulation.” Return to text.

- “EU Methane Reduction Regulation.” Return to text.

Thumbnail Photo Credit

Gordon Leggett, LNG Tanker GULF ENERGY, May 20, 2023 (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2023-05-20_01_LNG_tanker,_GULF_ENERGY_-_IMO_7390143.jpg.